British Art at War

Episode 1

Paul Nash: The Ghosts of War

So if you didn’t know already Andrew Graham-Dixon is my idol, to such an extent that I am watching a programme I have little knowledge of or interest in just because he is presenting it. Also I would like to not be such an ignoramus and learn about new artists.

British Art at War explores painting through the eyes of three artists during the World Wars. In the first episode Graham-Dixon looks at Paul Nash (1889-1946). He was a quiet and unique painter who always returned to nature in his art. Interestingly he never painted himself. The English countryside and woodlands had been an inspiration for him ever since childhood. For Nash nature represented youth, memory and comfort, it was an idyll. He attended evening art classes while working as a book illustrator. Nash moved to London in 1910 where he attended the Slade School of Art. His classmates included Ben Nicholson and Stanley Spencer. But Graham-Dixon suggests that the young Nash didn’t fit in. His tutor, Henry Tonks, derided him for his inability to draw the human form. So after a year he left and sucessfully orchestrated an exhibition of his own. In 1914 World War I broke out. Nash was keen to enroll, and signed up with the Artists Rifles. He was sent to the Front in Ypres with the Hampshire Regiment, armed with a pencil and a gun. He wanted to see war, to experience and depict it first-hand. But after falling into a trench and breaking his ribs he was sent home, a fortuitous turn of events as shortly after his regiment was killed in battle. He never spoke of his comrades, but The Cherry Orchard (c.1917) has something of mourning about it. Trees lined up like crosses in a graveyard, surrounded by a wire fence, it has a silent mood interrupted only by swooping birds.

Undeterred by his time in the trenches he longed to return to soldiering, and after petitioning he was made official war artist in 1917. His images of war aren’t the scenes of bloody carnage that we might expect. They are artificial looking, unnatural or dream-like. Wire (1918) shows damage and destruction, the aftermath of war being the ruin of nature. It is a mangled mess of barbed wire, debris and smoke. The tree’s branches are barely discernible from the entangled wire. Presumably the bodies have been cleared away. Nash focuses on the landscape not the people, an allegory for what humans have not only done to the land, but to each other. Similarly, We Are Making a New World (1918) is an ironically named battle-scape, where nature is symbolic. The charred and scarred remains of the countryside under the blood-red clouds represent suffering and death. Nash wrote to his wife from the Front that he saw himself as “a messenger, who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on forever…it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls”. He goes through a stylistic change too, a response to what he was going through and what he wanted to express. War changed landscape, and going to war changed his perspective.

Returning from war he found a different mood to modern art. Notably the surrealists began working in Europe around 1920, and Nash found admiration for De Chirico. Undoubtedly feeling inspired by the new styles of art Nash founded the Unit 1 movement, which included Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and old school friend Ben Nicholson. Nash wanted British art to have a purpose, one that was contemporary and forward looking, not bound by tradition and academia. It was experimental and free in spirit, but short-lived (1933-35). Perhaps working collaboratively didn’t work for Nash, but it injected some much needed modernism into the London art scene. Suffering terribly from asthma Nash left London for the Wiltshire countryside. Here he found inspiration in the Avebury stones, perhaps their elusive, alien-like qualities appealed to Nash. Graham-Dixon suggests that for Nash these forms could be his outlet for expressing the physical trauma, they are haunting, ghost-like. Equivalents for the Megaliths (1935) shows both the influence of Surrealists like De Chirico and the inspiration his new environment gave him. It is a dream-like image, where the landscape co-exists with geometric three dimensional shapes instead of the monolithic Avebury Stones. The cylinders and strange screens The hill in the background (surely a long barrow) and golden rolling hills give a depth to the painting that the shapes do no adhere to. They seem to rest on top of the field.

Nash’s next move was to Swanage another place that would provide artistic inspiration. His wife gave him a camera with which he obsessively captured nature and the coastal landscape. He was experimenting with a sense of form and rhythm in nature, an energy and movement not before seen in Nash’s works. He included ‘found objects’ in collages, all the while using photography as the basis for his work. At the outbreak of WW2 Nash was called upon to be a war artist once again, this time to capture the British air force. He moved to Oxford, and his obsession with aviation, birds included helped him to create such works as The Messerschmidt in Great Windsor Park (1940), Bomber in the Corn (1940), and The Battle of Britain (1941) . He sketched in aircraft dumps, a kind of graveyard for planes . Totes Meer (Dead Sea) (1940-41) is a monumental painting. The wrecked German planes blend into the landscape, a sea, suggesting that what once was a threat is now dormant even part of the history of the place. It is a weird image, it attracts you with the eeriness of it. The choppy wave-like hills composed of broken planes, the beacon of a half moon once again evoke a dreamy atmosphere. The owl, perhaps a symbol of Minerva the Goddess of wisdom, flies over the aftermath of war towards the horizon. The image is infused with meaning, but meanings only Nash could have portrayed.

At this time Nash was increasingly suffering from asthma, and so he returned to the Whitenham Clumps, an idyll from his childhood. Although pretty much bedridden he observed the landscape through binoculars, capturing the woodlands at night. He obsessively painted sunflowers, perhaps symbolic of happiness or spirituality. Since his youth his perception had changed, he had seen so much. Now coming back to this familiar place in declining health his mind was rejuvenated, proving to be a comfort to him in the last days of his life.

Episode 2

Walter Richard Sickert: The Theatre of War

As a young man Walter Richard Sickert wanted to be an actor. By 1915 he was world’s most famous painter. At the age of 21 he began studying at the Slade School of Art. He wasn’t an academic by nature and only lasted a year. He then became an apprentice to the great James Abbot McNeill Whistler, who proved to be an inspiration to the young artist. Sickert’s eye for the theatrical meant that his compositions had a staged look, quite often carrying an ambiguous narrative which was to become a stylistic trait. Wikipedia says Sickert is ‘considered a prominent figure in the transition from Impressionism to Modernism’, but I think he is much more complex artist than that.

The Music Hall or The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror (1888–9) Walter Richard Sickert, oil on canvas, Musées de la Ville de Rouen

Sickert did not go to war, he was too old to enlist; instead he chose to paint those left behind and their lives, showing that war was not confined to the trenches. He wanted to depict real life not sentimental images, the fashion of ‘art for art’s sake’ which was so popular in British art of the nineteeth century. Music Hall or The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror (1888–9) shows the profound influence of Whistler on Sickert at the start of his career. Centre stage is a lone entertainer in striking scarlet with an off-white hat, her mouth wide in song. She stands in profile with rounded shoulders, one leg behind her as if in mid-movement. But the rest of the image is quite strange. There is a dislocation from the background, a refraction of the viewer’s perspective of the subject through a mirror. Something strikes me as a bit morbid. The three spectators are elderly, one is attached to breathing apparatus. The atmosphere is stuffy and dark, contrasting with how the singer is lit up in warm vibrant colour. It is a portrayal of city life, escapism perhaps from the depressing normality.

Another scene of this kind is Ennui (1913). We are looking in on a private domestic interior, a man and a woman inhabit it, but it is the atmosphere which seems to be the subject matter. Maybe something has just happened, angry words have been said perhaps, a situation where the two have disconnected from one another; the woman in boredom or exasperation, the man in a nonchalant, almost self-satisfied mood. The title means listlessness or dissatisfaction, a lack of excitement. It is only the woman who embodies this word. She leans heavily against the chest in the corner of the room. She appears to be staring into space, at the wall or perhaps looking at the bell jar of stuffed birds. A metaphor for imprisonment, further contributing to the airlessness of the room. Her face is undefined. That of the man however is quite detailed. We can read his expression. He sits before a table, on which is a glass, half-full or half-empty of water or gin. The setting is comfortable, but the atmosphere is not. In 1913 the world was on the brink of war, this unease is perhaps a reflection of what is going on here. Of all Sickert’s works this is the most traditional in the sense of Victorian narrative painting, and he painted the scene several times, each slightly different. But it remains open to interpretation.

Despite Sickert not actively serving in the war he obviously could not help being affected by it. Soldiers of King Edward the Ready (1914) is an imagined depiction of soldiers in action, and we know that Sickert was pro-war, seeing it as a necessary evil to conquer the German threat. This scene shows men fighting for the cause of good, three soldiers poised with guns forming a diagonal line across the canvas. A man lies dead beneath them. The composition is strange in that it is a shallow space, lengthwise the ends of the guns are cut off and what they are pointing at is not shown at all. Subsequently Sickert declined the offer to work for the British War Memorials Committee.

Brighton Perriots (1915) is an interesting painting. At first sight it is just a performance on Brighton pier, but the year in which it was painted Britain was at war. The usually popular holiday resort would have been deserted. The performers are gaudily dressed and the sky is tainted with a reddish-pink, perhaps symbolic of the bloodshed happening elsewhere. The people are faceless. It is totally unlike the traditional Victorian painting, the subject is not of social accord and wealth, of grand tales of history or myth. Instead it is ordinary, existential. But knowing the context of the painting shines different light upon it.

These four paintings illustrate not only Sickert’s strong stylistic development, but the continuation of creating scenes from his own perspective, almost unattached from tradition and rules of painting. I have purposefully omitted any of his nudes, mostly because they are many but also because I would like to do them justice and write about them as a separate thing. In relation to war Sickert did something very unique with his work during the period, almost focusing on the negative space, what was left behind after the soldiers went to war perhaps never to return. Always infused with uncertainty, anxiety and a feeling of discomfort he depicted the disconnection and the isolation between people.

Episode 3

David Bomberg: The Prophet in No Man’s Land

The early 20th century brought a wave of change in terms of technology, industry, and society; and a new art was required to reflect this. David Bomberg pushed art to its limits. In 1911 he enrolled in the Slade School of Art. However he was not a natural academic and after receiving criticism from the infamous tutor Henry Tonks and hitting him with his palette he was expelled. However some good came of his time there, as he met artists like Walter Richard Sickert who would prove to be an inspiration to the young Bomberg.

He soon started to create stylistically original stuff, like Vision of Ezekiel (1912), which was painted after the death of his mother. Consequentially it is the same year in which an exhibition of Italian Futurist art was shown in London. It is a strange image, the struggling jumble of bodies are abstracted to the point of blocks. Graham-Dixon perceives a Jewish representation of life, death and Heaven. Whatever the meaning, it totally rejects tradition and it marks the advent of British modern art.

In the Hold (1913-14) was created after leaving school is another radical landmark work. Again it is totally unique. Although at first it seems a kaleidoscopic canvas of colour, a closer look shows the hold of a ship with figures within. It is so radical and fresh compared to the traditional stuffy upper class painting of wealth and privilege of the preceding period. It was a new way of perceiving the world. This new mood was being pioneered by such artists as Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticists, a reactionary movement expressing feelings and opinions towards politics and current world events. They found that realism was an inappropriate mode of communicating their messages, instead opting to use the positioning of geometric boldly coloured forms. This painting adheres to their rules, expressing an influence on the artist.

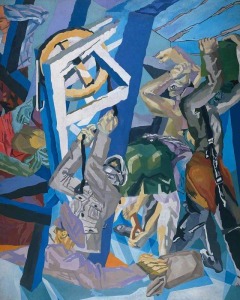

Study for ‘Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi’ (c.1918-19) David Bomberg, oil on canvas, Tate, London

At the outbreak of war of in September 1914 Bomberg enlisted in Royal Engineers and was sent to fight at the Somme. After two of his best friends were killed at the Front he shot himself in the foot and was sent home. But he didn’t do it out of cowardice; he was suffering mentally from his experiences, which his poems and sketches of the time clearly show. Being involved in war gave him a different perspective of life, and he once again began seeking new order and satisfaction for his art. Sappers at Work (c.1918-19) for which this is one of many studies, depicts a group of Canadian engineers who dug tunnels under the German front line in which to lay explosives. Each figure shows strain and tension, they are hard at work. Graham-Dixon insightful points out that the composition draws from Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St Peter (1601), specifically the figure in the middle who we see from behind, bending down with green shorts on. The angles and forms are very sharp, creating an overall feeling of industry or perhaps hinting at the future debris of the bombs. As a tribute it does not strike me as very commemorative, the identity of the sappers has been obscured by hiding their faces. Perhaps it is a statement that heroes could be faceless.

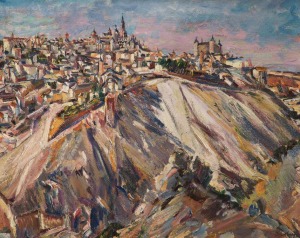

The following years saw Bomberg working in Jerusalem, Palestine, and settling in Toledo in Spain. The town El Greco lived in for the last thirty-odd years of his life, the landscame provided Bomberg with a source of solace. The paintings from this time show expressive brushwork, a different tonal palette, and are released from the strict geometry of his early works. Images like Toledo, Spain (1929) show an overwhelming sense of the nature, almost sublime, the scale and colours could be seen as therapeutic. But this period of peace did not endure.

Civil War in Spain meant returning to England, and back in London in 1937 Bomberg became introvert, painting himself over and over again. He stopped painting for a while as World War broke out again. A series of the city of London including St Paul’s and River (1945) is a charcoal sketch which shows another shift in style. This time the effects of speed and atmosphere are at the centre of the images. There is something of the Futurists about this work, it is immediately dynamic and modern. The use of charcoal to depict a smoggy fog, or perhaps Blitz-induced smoke hanging in the air.

Bomberg died in London in 1957, after a failed attempt to revive a school, firstly the Borough Group which was a short-lived fellowship of artists, and then setting up classes in Spain. But his commitment to art continued to inspire artists, a continuous movement forward, always responding, always inventing.

Although there are common themes between Nash, Sickert and Bomberg the three are quite radically different in terms of their experiences of war. They all responded to it in a personal way, although Sickert was the only one to have avoided active service. Nash translated it through nature and metaphor, Sickert focusing on life at home, and Bomberg in a reactionary, futuristic manner. I think the similarities and contrasts of the three painters give a sense of change during the years of World War; an impending sense of uncertainty, anxiety, trauma and the aftermath of conflict. All three artists portray a feeling of depression, Nash and Bomberg obviously dealing with the mental effects of life as a soldier. I must admit that I had little prior knowledge of these painters, but I have found an appreciation for the art they made and the progress they contributed to modern British art. All three were pioneers, all different stylistically but their cause was the same; to create a new form of expression relevant to the times they lived in. Without them we certainly would not have had artists like Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and Henry Moore. And of that we have to be grateful.