Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece

Until 29th July 2018

British Museum

Auguste Rodin (1840 – 1917) may have been a ‘modern’ man but it is clear from looking at his sculptures that he was intensely inspired by the past. He said ‘Antiquity is my youth’, betraying a deeply rooted respect and admiration for the ideas and aesthetics of Ancient civilisations. This exhibition seeks to investigate Rodin’s relationship with Classical sculpture by juxtaposing his creations (drawings and paintings as well as sculptures) with artefacts he amassed and displayed in his studio home and the collection of the British Museum, which he knew and loved so well.

Pheidas (c. 480 – 430 BC) is the most famous of the Ancient Greek sculptors because of his contribution to the carvings of the Parthenon, some of which were brought to Britain in the 1800s by Lord Elgin and later purchased by the government for the British Museum. It was these marbles that had the greatest influence on Rodin’s development as an artist and sparked a love for the museum when he visited London in 1881. He returned to see the Elgin Marbles there several times before he died in 1917. Although he never visited Greece, these sculptures would prove to be an obsession and a constant source for his creative energy.

Rodin’s own copy of his marble sculpture The Kiss (1898) is at the beginning of the exhibition and is more captivating than I thought a plaster cast could be. The subject is derived from that great Italian masterpiece of literature, Dante’s Divine Comedy. The doomed lovers Paolo and Francesca are frozen in a moment of physical desire. But Rodin also captures a tangible feeling of the psychology of love in the way the bodies meld into one another, portraying the essence of complete passion. There is a graceful fluidity and balance of weight, that paired with the contrast of smoothly worked and roughly hewn textures echo Michelangelo‘s hand. Rodin saw his works in the flesh when he visited Italy in 1875, writing of the experience that ‘Michelangelo revealed me to myself, revealed to me the truth of forms.’ What I love about this work is that although we cannot read the expression on the faces of the entwined couple, we can picture them in our mind, so readable is their body language. The cast is beside a pair of Goddesses from the Parthenon whose bodies are similarly responding to one another. They are separate yet interlocking in a coherent and descriptive relationship, the musculature exposed and concealed by the drapery gives movement and expression.

The Kiss (large version, after 1898), plaster cast from first marble version of 1888–98, © Musée Rodin

Goddesses in diaphanous drapery, figures L and M from the east pediment of the Parthenon (about 438–432 BC), marble, © The Trustees of the British Museum

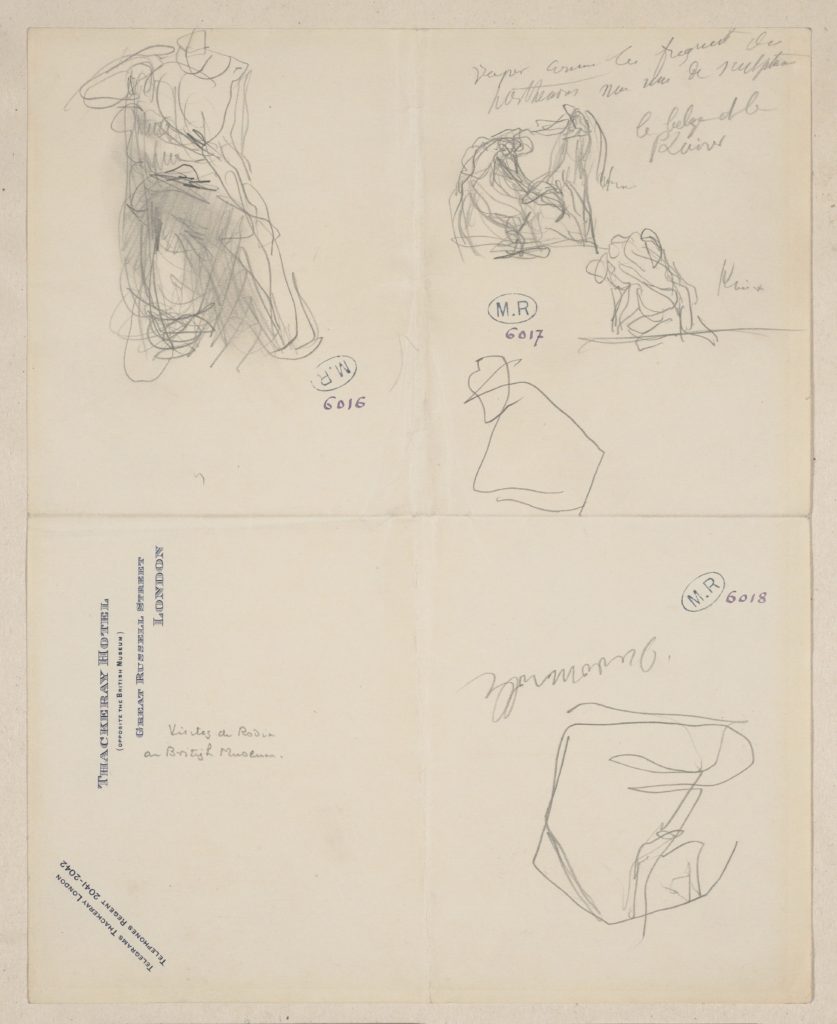

One of the things I find to be the most interesting part of an artist’s work is their drawings. Putting pencil to paper is an instantaneous and intuitive process, showing the inner workings of the mind. Rodin drew from the Parthenon sculptures that he saw, assessing their mass and deconstructing their forms in an analytical way. His mastery of the three-dimensional medium is clear in the way he almost seems to mould the marble to his vision, something that is obviously impossible. The sketches for what is known as Goddess Rising, figure K demonstrate his ability to bring something to life through dynamic movement, just as Pheidias did. These quick sketches of the Parthenon sculpture are lively and modern in their freedom, uncovering how he could think in shape and volume. Being fragments took nothing away from his appreciation of these Ancient sculptures, a sentiment was shared by the great Antonio Canova, who was asked by Lord Elgin to ‘restore’ the marbles and, quite rightly, refused. Both sculptors felt that their being incomplete made them no less of a masterpiece.

Sketches including figure K from the Parthenon and a metope from the south side of the Parthenon, 20 February 1905, graphite on paper © Musée Rodin

Rising goddess, figure K from the east pediment of the Parthenon, about 438–432 BC, marble, © The Trustees of the British Museum

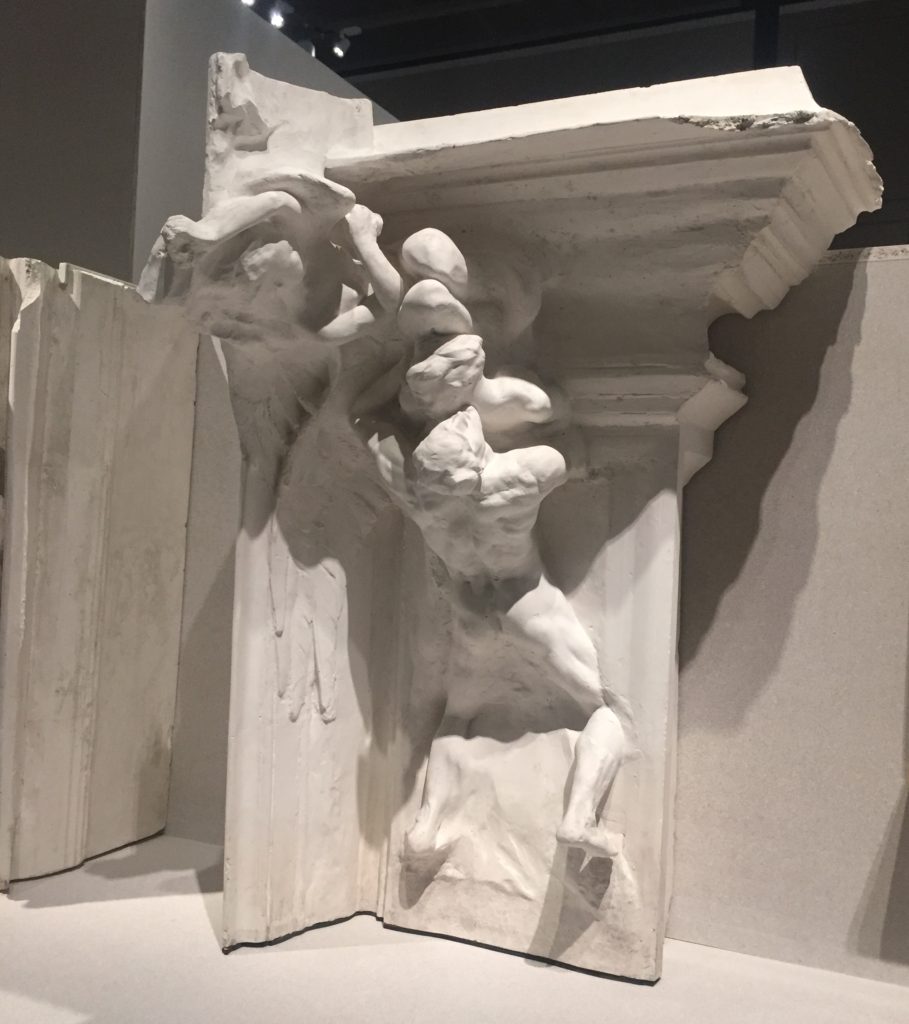

The Gates of Hell were originally going to feature The Kiss, but the figures were removed through the working revisions. Commissioned for the French State, the colossal doors were intended to be the entrance to unbuilt Musée des Arts Décoratifs, where the Musée d’Orsay now stands and where plaster versions of the doors now live. Although never completed, the preparatory models show the influence of the Lorenzo Ghiberti‘s doors to the Baptistry in Florence. The gates were to be cast in gilt bronze (another nod to Ghiberti’s masterpiece) interweaving the traditions of sculptors past into his own distinct visionary style. In the plaster mock-ups such as the detail below, Rodin pushes the material to the limits to create a truly staggering sensation of dimension and movement. The plasters and various studies demonstrate Rodin’s cognitive development of the monumental idea.

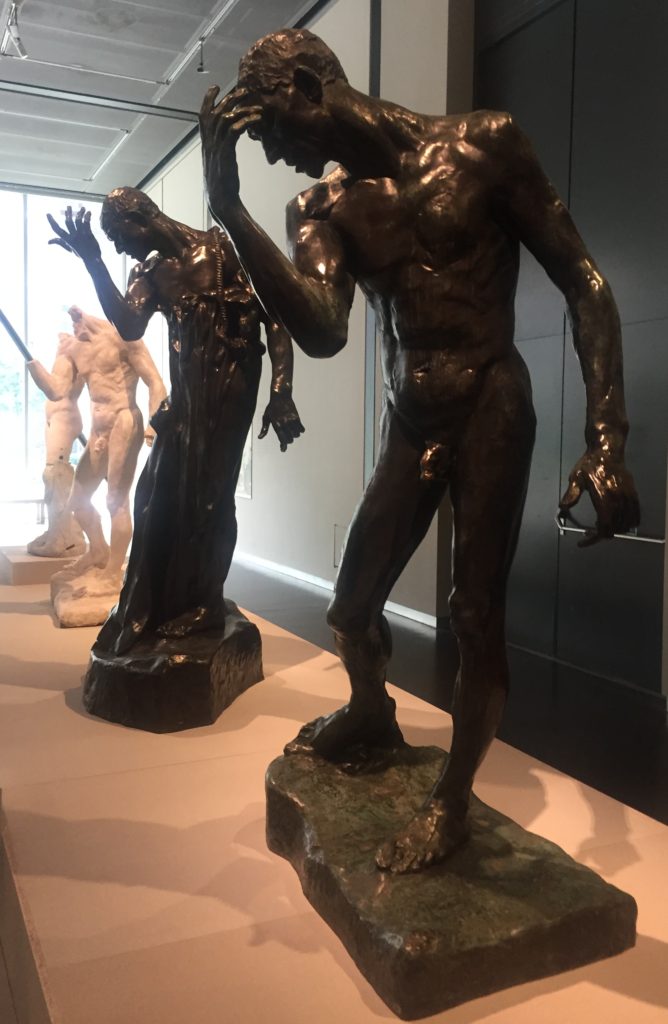

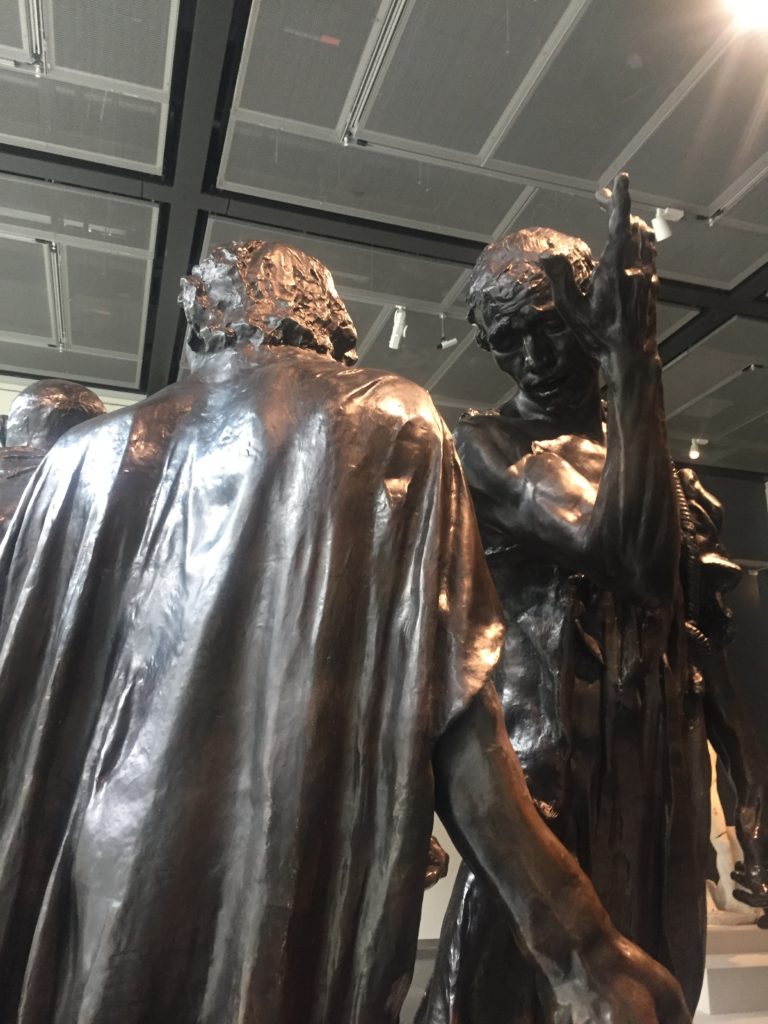

Considered by many as his magnum opus, this cast of The Burghers of Calais (cast 1908) is on loan here from its home outside the House of Parliament. Commissioned in 1885 it depicts six high-ranking citizens of Calais who gave up the keys of the city and their lives to end the Hundred Years War. Each of these heroic men exudes a different emotion facially, but also through their bodies. Rodin studied the human form first from nude models, then exaggerated limbs and body parts to amplify meaning, for example, the head and hands of Pierre de Wissant (photos below). The prolific Rainer Maria Rilke wrote in 1902 that the pose of Wissant shows him ‘passing through life’. As he moves forwards he turns back, ‘his hand opens in the air and lets something go, something in the way in which we set free a bird. He is taking leave of all uncertainty, of all happiness still unrealised.’ Although each individual is enveloped in their own particular display of emotion and grappling of their fate, as a group their gestures and stances flow like a kind of slow and sombre dance. Being at ground level (as Rodin intended) pulls the viewer into the circle of doomed men, allowing us to come face to face with them. By doing this he moves beyond the Classical purpose of sculpture. The Parthenon marbles were not to be interacted with in this way, but displayed up high to be revered and worshipped, eternally untouchable ideals. Rodin pairs his knowledge of anatomy with his understanding of the significance of poses and gestures to turn the human body into a language in itself. Energy reverberates through the group, torsion in their bodies creates the feeling of life, but it is balanced with weight and silence. There is something reminiscent of Bernini in the way the pinnacle of drama and emotion has been encapsulated, paused and emphasised. The men are dignified and caught up in an internal debate. Dressed in sackcloth and shackled by ropes and chains, they have a strong presence in the room. ‘I intend my art to express the spectrum of emotions, from the height of ecstasy to the depths of agony… The body is a cast which bears the imprint of our passions’ said Rodin, nailing what it is that we are seeing beneath the bronze. At the core of the story it is the human condition under examination here; the greatest of sacrifices, self- sacrifice, is the price of peace for the city (the men’s lives were eventually spared). It took the sculptor 11 years to complete the group, an indication of how Rodin wrestled with the subject, working and reworking until he was satisfied.

There are over 80 works on loan from Musée Rodin, sculptures in marble, bronze and plaster, as well as Rodin’s own collection of around 6,000 fragments from Antiquity. Displayed around his home studio he would show them to his visitors. He said ‘At home I have fragments of gods for my daily enjoyment…Contemplating them brings me the happiest of these stolen hours from which the Ancient world always speaks to me.’ These objects fuelled his obsession with the past, one that brought him personal pleasure as well as being aids to his work. He also collated photos and postcards in scrapbooks, some on display here, annotated and well-thumbed. Seeing the way he drew from his collection and that of institutions such as the British Museum, through drawings, models and finally to the conception of his own ideas it is clear to see how he absorbed lessons from the sculptors of Antiquity and without fully imitating them, captured their essence in his own work. He very much saw himself as part of a great tradition, a continuation from his master Pheidas. His affinity with his predecessors can be seen in the belief of sculpture as a timeless and eternal artform. But Rodin was a philosophical artist, infusing the ideas of his time and own unique mind into what he created. In 1905, towards the end of his life and as a rich and famous man, he remained humbly indebted to the past, saying ‘I invent nothing, I rediscover.’