Brothers in Art: Drawings by Watts and Leighton & Julia Margaret Cameron

Brothers in Art: Drawings by Watts and Leighton

Watts Gallery until 19th February 2016

Julia Margaret Cameron

V&A Museum until 21st February 2016

To catch up with my lack of gallery visit over Christmas and January, I saw a couple of exhibitions which are closing soon. It was good to see them in succession like this because not only were they both Victorian but also they were closely linked. The Brothers in Art: Drawings by Watts and Leighton explores the working relationship and personal friendship of two of the leading artists of their day. The inspired title comes from a letter by Watts’ wife, Mary Seton Watts, who describes the men in a letter, describing their collaborative spirit and mutual admiration. Watts had a humble upbringing and suffered from illness as a child, whereas Leighton came from a reputable family, but both showed a love of drawing from an early age; Watts from his sickbed and Leighton travelling the continent with his family. From the earliest sketches it is clear that both artists were inspired by the Classical and Renaissance eras of Italy. Study of a Female Head from Raphael’s (1828) is an exquisitely and faithfully drawn copy that Watts had taken from a book, done at the age of 11. It shows a respect for the Old Master, every line has been carefully considered and placed. But while Watts could only copy from books, Leighton had trained under established artists and even studied at Florence’s esteemed Accademia.

‘Study of a Female Head from Raphael¹s Transfiguration’ (1828) by George Frederic Watts, chalk on paper, Watts Gallery Collection

A letter to the ‘Signor’ from ‘Fred Leighton’ praises the genius of Watts’ ideas, which paired with his particular style sets him apart from his contemporaries. Although Leighton is sometimes grouped with the Pre-Raphaelites he is, like Watts, very much his own man. They were staunch believers of studying from the Antique, and that drawing from life as the foundation of all art. Drawings show the workings towards a final finished painting, and a selections of small sketchbooks on display are like diaries, giving us snippets of the creative process. Watts advised art students to draw constantly from drapery, as it would provide the textures and tones required to create convincing forms. At the Royal Academy of Arts Leighton prescribed life drawing classes specifically for the practice of depicting clothes on a living body.

In a ‘Study for Return of Persephone’ you can see how Leighton, creates movement and drama purely through the depiction of a silky sheer Greek-style dress. Using just white and black chalk and the colour of the paper beneath, he creates a solid body whilst only focussing on an expanse of fabric. The delicacy and accuracy of line is something that he captures perfectly in both pencil and paint.

‘Study for ‘Return of Persephone’ (c. 1890) by Frederic Leighton, black and white chalk on brown paper, Leighton House Gallery, London

Living in a world of ‘selfies’ I often feel that photography has become something of a lost art, that rather than advancing the exact opposite has happened. Instead of being amazed by the beauty of an image, or inspired by the process involved in taking a photograph, everything looks fake. The uncountable number of airbrushed and filtered images that we process every day, instantaneously absorbed as we scroll through intangible glowing squares is actually quite disturbing. Walking into this exhibition I was struck by the simplicity of the first few images. They were raw in that you could see the work that had gone into them, both the physical and creative process. I love that Cameron’s confidence as a photographer can be seen by walking around the gallery, she becomes more serious without losing any sense of self.

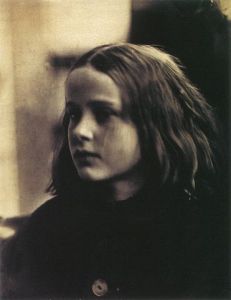

It was at the age of 48, when given a camera as a present from her daughter and son-in-law that Cameron took up photography seriously. The accompanying note read ‘It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude’. Annie, My First Success (1864) shows a creativity that was to become the enduring energy throughout her career. Capturing the characters, whether real or acted, of the friends and family who sat for her was what she did best. Annie, the daughter of a neighbour, appears as an angelic almost spectral figure. I love the layers of light and dark, the way the eyes are obscured, and the flaws on the surface.

Annie, My First Success (1864) by Julia Margaret Cameron, albumen print, National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

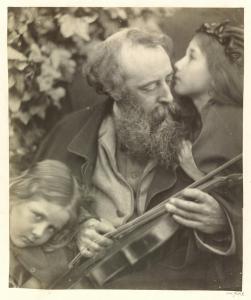

The image below is of The Whisper of the Muse (1874), and is of her dear friend G.F. Watts. Two little girls are posed around him, one whispers into his ear, perhaps some inspiration for music that he is about to play with the instrument. Cameron wrote that ‘Mr. Watts gave me such encouragement that I felt as if I had wings to fly with’. The circle of artists and literary figures around the photographer were supportive of one another, and often feature in each other’s works. Photography was a relatively new art form, still quite primitive in its method. Taking a photograph was hard work, and would often result in unusable images. Today we can capture an image at the touch of a button whenever we choose. But for Cameron it was often an experiment, an artistic evolution.

The Whisper of the Muse (1874) by Julia Margaret Cameron, albumen print, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Sentimentality is a quality that comes across in all Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs, for which she was sometimes criticised. But I think that this is her strength, her feelings are conveyed through her photos, just as a family album would. She has an eye for poetry, even her portraits tell a story. She was inspired by her contemporaries and the Old Masters, and this comes across in her work. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, Cameron is allowing us to view it through hers.

While at the V&A I went around the recently opened Europe galleries, a beautifully curated collection of art and artifacts from 1600-1815. I could live in the seven Baroque and Rococo themed rooms; opulent marble busts of Catholic clergy, gilt mirrors with more flouncy scrolled frame than glass, and clothes from a time when men wore stockings and embroidered silken suits. I particularly loved the recreation a seventeenth century panelled room from the Château de la Tournerie, France, which I sat in for a while and absorbed the atmosphere and old woody smell. Another highlight was a display of beautifully crafted guns, accompanied by an enlightening video about the development from wheel-lock to flintlock mechanisms (also here http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/galleries/level-0/room-5-the-rise-of-france,-16601720/). I will definitely be returning to the galleries at the next available opportunity.