Giovanni Battista Moroni

Royal Academy of Arts, London

25 October — 25 January

If you have never heard of Moroni then you are in the same sorry position that I was in until a few months ago. Reviews of the exhibition call him ‘revolutionary’ and a ‘genius’, but throughout my study of Art History I had never come across him. Comprised of a beautiful selection of Moroni’s religious works and portraits (for which he is best known), this exhibition is urgently overdue to enlighten the ignorant like myself of this long-forgotten artist.

Giovanni Battista Moroni (c. 1520/24 – 1579) was undeniably one of the great portraitists of the Sixteenth century. He studied under Alessandro Bonvicino (also known as Il Moretto da Brescia) Cinquecento exponent of Giorgione, and from his early works it is clear that Moroni influenced his peers. His own style quickly evolved absorbing the principles of masters like Titian, the great Venetian colourist, with whom he once met. Moroni gained relative wealth and reputation during his career, especially in his hometown of Bergamo where he was regarded as the most famous portraitist. Moroni worked for the Church during the age of the Council of Trent, winning prestigious commissions for altarpieces. The Council selected artists to defend the faith against the challenge of Protestantism. Lorenzo Lotto, Moroni’s predecessor had already begun modernising religious images to reflect the changing demands of the Church, and Moroni can be seen to continue this. The religious works here at the RA have a strong traditional style, one which is not unfamiliar in works for the Catholic Church during the 1500s. Despite being unable to resist the stylistic inheritance of his peers, Moroni at once stays true to his Lombard roots and creates artworks which are identifiably his own.

One such work is A Gentleman in Adoration before the Baptism of Christ (c.1555-60). This concept of depicting someone witnessing biblical events has been seen many times before, but Moroni’s interpretation has a rare immediacy and proximity. Illusionism of this kind was specifically designed to evoke extreme piety on a physical level. And the exact thing the Church was looking for as visual propaganda to strengthen its foundations and revive the fervour of worship. Here we see a gentleman, who we stand beside, and with him we look out at the holy scene of the baptism of Jesus. We are a few feet away from Christ and St John the Baptist (although the perspective would suggest otherwise). The rocky landscape (surely a view of Lombardy with its mountains and hills) has a strong colour scheme; the blue-greens of the background contrast with the striking red and white robes of the holy figures, and the golden light surrounding the holy dove. The gentleman is dressed soberly in black, probably the donor of the painting, a colour reserved for the rich and professional classes. The rugged stone wall behind him provides a barrier between the sacred and the worldly. His hands are posed in prayer, imitating those of Christ’s, and he looks on the scene with a serious and attentive expression. And this emotion should be mirrored in us as we share this view. This painting would have been made for private devotional use, perhaps to practice the spiritual meditations promoted by Jesuit founder Ignatius of Loyola in the 16th century. His book published in 1548 provided exercises to strengthen one’s relationship with Jesus and to help lead a life of devoted to Him. It included solitary prayer and particular reflection on the life and passion, conjuring images in one’s mind. This focus on the visual was further aided by paintings like this one, providing an emotive and realistic scene to concentrate on whilst reflecting introspectively.

A Gentleman in Adoration before the Baptism of Christ (c.1555-60) oil on canvas, private collection of Gerolamo and Roberta Etro

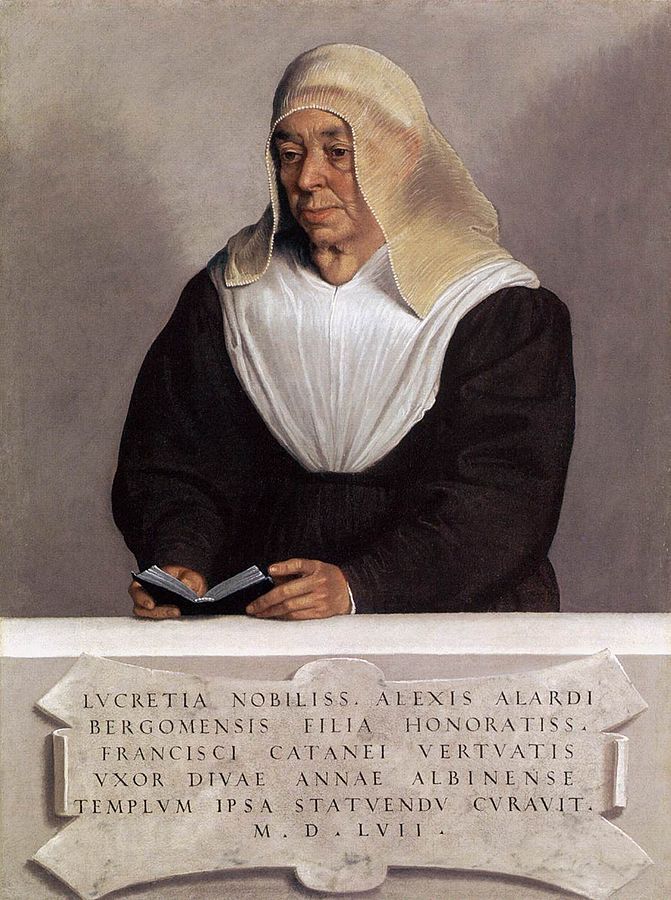

The next painting that I wanted to mention is the Portrait of Lucrezia Vertova Agliardi (1557), which contrasts so profoundly with the grander portraits in the exhibition. Set against a plain wall, behind a stone monumental plaque is the sitter in 3/4 length. The inscription helpfully tells us who exactly she is; Lucrezia, daughter of the most noble Alessio Agliardi, wife of the most esteemed Francesco Cattaneo Vertova, personally supervised the building of the church of Sant’Anna at Urbino, 1557′. The very fact that Moroni has gone to the effort of explaining this to us could be seen two ways; firstly, as a simple abbess she needs introducing, and without this text the average public viewer would not have known who she was. Secondly, as a commemorative painting the plaque serves as a memorium. She is elderly, perhaps her health is failing. Her deeply wrinkled face and loose skin is complemented by the crinkling of her veil and smock. She has a large goiter-like lump on her neck. She looks weary but not unhappy. Instead of meeting our gaze she looks away, her attention is held elsewhere. She has not been idealised but nevertheless she emits a sense of strength, austerity and devotion to her cause, cutting a figure of admiration and respect. The glint in her eye gives her an emotion which makes her accessible to us as a viewer. This is what you could call a ritratto esemplare, an image painted purely to honour the subject, not a public display of vanity and status.

This next painting is very different to that of Abbess Agliardi, Portrait of Prospero Alessandri (c.1560). This format of portrait became the default of Moroni during this period of his career. He had become a reputable, in-demand artist and painted numerous images of the local aristocracy. The subject was usually depicted against an architectural backdrop, comprised of aged stone walls and pillars, a glimpse of a rural horizon beyond. The inclusion of architectural features may be a homage to his father’s profession, and compositionally they follow in the wake of his tutor’s established portrait style (interestingly Moretto was the first Italian artist to do a life size full-length painting). The poses are relaxed but exude authority. It is notable that although Bergamo and the feudal region of Lombardy was then under the jurisdiction of Venice, it was closer to Milan which was ruled by the Spanish. Moroni’s works of the early 1650s show a visual melding of these influences, specifically in the clothing. And this is the first thing I notice about the portrait, and of those in the same room; the fashionable dress. The displays of the latest styles in the most luxurious fabrics are a testament to the sitter’s wealth. Only the rich and powerful wore black. With Signore Alessandri here, his black doublet further enhances the white of his lace collar framing his face, and the illuminates the very fetching pink of his breeches. It gives him a strong silhouette. His sleeves are slashed and adorned with golden ribbon in a grid-like pattern, adding an element of geometry to the picture. It is an informal portrait, set outside with the subject leaning against a stone block. Carved in Spanish upon this plinth reads ‘Between hope and fear’, his family motto, which gives the impression of ancestral heritage. Not just any old family had a motto. The later added inscription ‘Son of Gerolamo, husband of Isabella Gozzi, daughter to Pietro’ add further to this feeling of establishment, presumably a contemporary would have been impressed by his connections. Contrasting with the boasting display of fashion and lineage is Prospero’s face. It is a noble face, but his expression is not demeaning. On the contrary he looks directly at us as an equal. Moroni usually knew his sitters personally, and a viewer we are extended this insight into their personality. In this respect one could be tempted to use the word ‘psychological’ to describe Moroni’s portraits, but this word did not exist in Moroni’s day. Perhaps a word like ‘attitude’ is better, explaining something that can be gleaned instantly from the look in someone’s eye or their posture . The rooms dedicated to portraiture in the exhibition have a mood of elegance and officiousness, but the bright colours, sumptuous clothes and expressive faces of his sitters give an impression of modernity and naturalism. There is no space between us and the subject, we are being placed right where Moroni was.

Moroni’s religious works show an artist who adhered exactly to the wishes of the Catholic Church, while aiming to make images relevant to the present time. He complied with the Council of Trent’s demands of art, using it as a visual tool to reinforce the doctrinal core of Catholicism. But it is through his portraiture that we get a sense of Moroni as a person; a simple and honest man, friend to aristocrats and lower classes alike, painter of human nature. Unusually for a portrait painter he did not paint himself. Despite this I came away from the exhibition feeling that I knew a lot about him. Without the need to idealise and embellish we get to see what Moroni saw, and this includes a personal insight into the sitter’s character. Moroni is new to me, which is a shameful confession but it signifies exactly what I love about Art History; that there is always something new to learn and someone new to discover.