“Open my heart and you will see, engraved inside of it, Italy”

When I get that familiar feeling of wanting to be instantly transported to Italy, there is only one place in London to go: The V&A museum. Their vast Renaissance galleries are filled with art and objects that temporarily alleviate that deep-rooted, tear-inducing withdrawal I feel for a county that Robert Browning and I call “my university”. I spent about two hours wandering around, sighing romantically at the treasures on display and took 150 photos, some of which I want to share with you.

Firstly, a work by my favourite sculptor, Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). This Baroque bust is of Thomas Baker (1606-58), the man believed to have been responsible for delivering Van Dyck‘s famous triple portrait of King Charles I to Bernini. A copy of the portrait hangs nearby. I love Baker’s hair, it is glamorously dishevelled with envy-inducing volume. The lace collar is miraculous and has been so exquisitely carved that you can see through it. In fact, from the shoulders down it is very like one of Van Dyck’s views of Charles I, even down to the arm posed as if in a sling.

This transported chapel of Santa Chiara is a marvel of the gallery. Originally housed in a convent in Florence, this altarpiece and surrounding structure is thought to have been designed by Giuliano da Sangallo (1443-1516), inspired by the style of Filippo Brunelleshi (1377-1446). It brings to my mind the Pazzi Chapel in Florence. Comprised of pietra serena, marble and glazed-terracotta it is a totally unique experience to have in the heart of London. The sculptures of St Francis and St Clare (Chiara) were significant to the nuns of the convent as they were the founders of the Franciscan order of the Poor Clares to which they belonged.

The Venetian painter Jacopo Tintoretto‘s (1518-94) Self Portrait (c.1548) is full of his personality. With dark soulful eyes that follow you, this forceful reflection has been painted with the characteristic vivacity that earned him his nicknamed Il Furioso, because of the energy and speed with which he applied paint to canvas. Legend has it that his apprenticeship under Titian ended after just ten days, perhaps because of the elder’s jealousy or the pupil’s unwillingness to be tamed. Self-portraits became popular in the fifteenth century, and progressively more so with the increasing availability of mirrors. Into the 1500s, they became an expression of the artist as a creative genius, giving an insight into his intellect and status.

Giambologna (1529-1608) was known as the ‘prince of sculptors’, and primarily worked for the Princes of the Renaissance, the Medici. This River God is probably a terracotta model for the Medici Villa in Pratolini, the god represents the power of water and nature. Looking closely you can see how Giambologna has used his fingers and worked with instinctual movement to mould the soft clay to create the elongated, muscular body of the deity and the contrasting fluidity of the water that pours from the urn he holds.

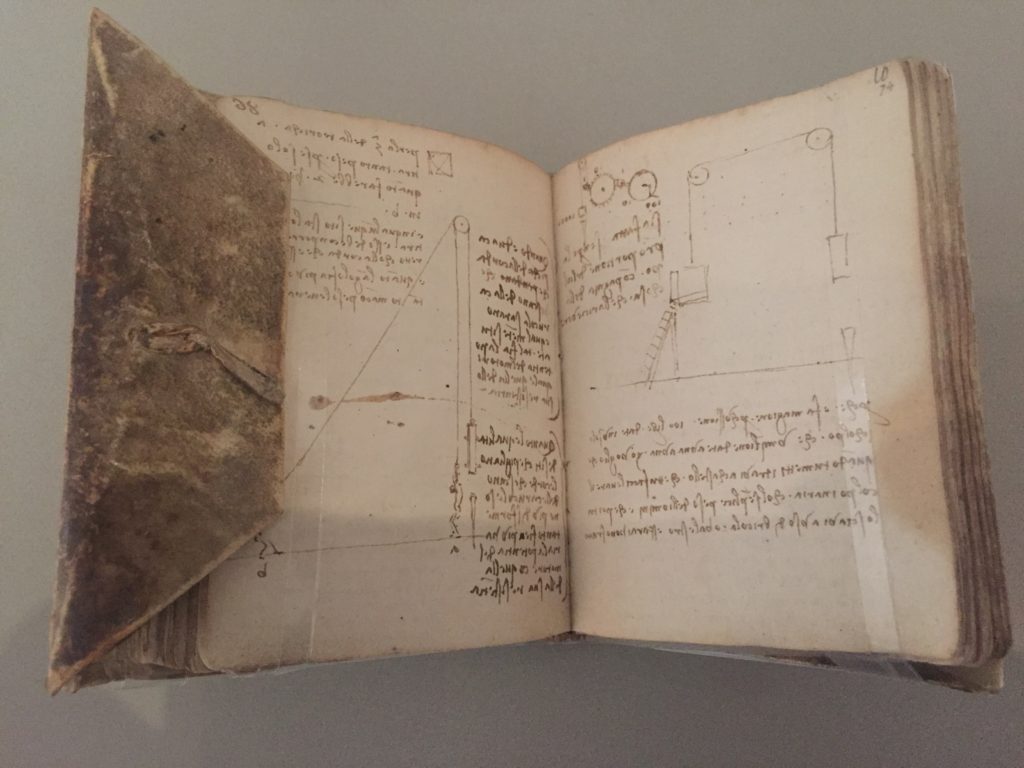

One object that I always get excited about seeing is da Vinci’s notebook (Codex Forster II2). I love to see his handwriting, left-handed and in his famous ‘mirror-writing’. The codex is displayed open on a page on which he has illustrates a pulley system, noting the theory and mechanics of its workings. It dates from around 1495-7 when he was in the service of Duke Ludovico Sforza in Milan, who commissioned da Vinci’s masterpiece, The Last Supper.

Praising the grace and delicacy with which the Florentine sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino (1486-1570) Giorgio Vasari records in his Lives of the Artists a work similar to this, made for the artist Pietro Perugino (1446-1523). The delicacy of the modelling and emotion that is tangible in the posing of the bodies is remarkable. There is weight and gravitas in the dead figures, especially that of Christ. Being removed from the crucifix by four men, he retains the shape of the cross to which he was nailed. I love the man crouching in the bottom right, legs braced under the weight of the corpse he is lifting. Vasari said of Sansovino that “Nature had endowed [him] with a great genius, so that he gave much grace to the things that he did”. This gilded wax model is an extremely rare and exquisitely beautiful object.

I have to finish this post with something from the V&A’s magnificent cast courts, which are currently being renovated. Aside from the Davids by Michelangelo and Donatello, my favourite thing in there is the copy of Giovanni Pisano‘s (1250-1314) pulpit for Pisa cathedral, completed after eight years work in 1311. It is decorated with scenes from the life of Christ and the Last Judgement, apt subject matter for a pulpit from which Catholic sermons were preached. Giovanni was the son of the great Nicola Pisano (c.1220/1225-c.1284), who is often credited with being the first truly modern sculptor. Giovanni trained under his father, and his virtuosity is such that his hand is often indistinguishable from Nicola’s. However, Giovanni did something new by seamlessly blending the traditional Gothic and antique Roman styles with a new focus on human emotion. This would contributed heavily to the yet unconceived Renaissance. The stirrings of a revival of Antiquity here are inspired by the decorative carving on Roman sarcophagi, seen in the panels around the top of the pulpit. Although the overall feeling is Gothic, upon closer inspection there is a clear attempt at naturalism and expression. I love the staircase, with the floating steps which so beautifully fuse the conventional with the innovative. The little bearded men that emerge from spandrel under the treads of the stairs are playfully Gothic, while the underside is Classically inspired, resembling an architectural console decorated with corinthian leaves and a rosette-embossed helix.