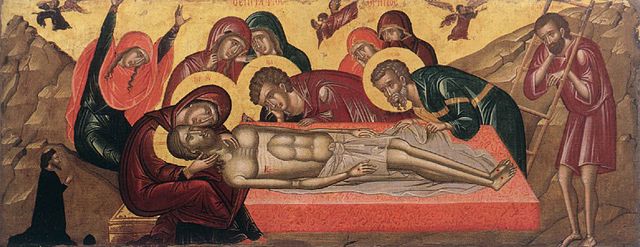

Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ)

Giotto di Bondone (1266/7 – 1337) is a man of mystery. We know very little about him but his huge influence on Western art make him a compelling character. According to Giorgio Vasari he was trained by Ciambue, who happened across him as a young shepherd boy drawing one of his sheep onto a rock. So impressed was the master painter that he took Giotto to Florence, where ‘in a little time, by the aid of nature and the teaching of Cimabue, the boy not only equalled his master, but freed himself from the rude manner of the Greeks, and brought back to life the true art of painting, introducing the drawing from nature of living persons’. This is quite a testament from the great Vasari. Today Giotto is more popularly known for designing Florence’s Campanile, but in terms of his painting he was a game-changer. Although not at once obvious to the modern eye closer inspection shows the revolutionary character which Vasari praised.

In 1304 Giotto was commissioned by Paduan moneylender Enrico Scrovegni to decorate the interior of his chapel. Usury was a sin so presumably he meant to atone for his family’s choice of career with a grand artistic gesture (in his Inferno Dante put Scrovegni’s father in the seventh circle of Hell). The Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ) is scene from the walls of the chapel’s fresco cycle. It is a subject often depicted in European art so we know the story and the characters. Holding Christ is the Virgin Mary dressed in blue. At his feet, which she had washed with her red hair, is Mary Magdalene. St John the Baptist stands with his arms outstretched behind him. The three create a triangle around Jesus, which come to a point at the faces of Mary and her son. To the right are two haloed saints, probably Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus who were present at the crucifixion. Curiously they are the only figures who do now show strong emotion. A group of mourners have gathered to the left of the picture, their grief reflected in the pixie-like angels suspended in the sky above them. Although lacking in texture and dimension the colours are beautiful, especially the ultramarine sky and pink tones in the clothing. The background is like a theatre backdrop, flat and unfussy, further emphasising the drama and emotion. Perhaps symbolic of the original sin a leafless tree stands upon a rocky slope, which almost divides the painting in half and creates a diagonal line, meeting our other triangle at the faces of Jesus and Mary. Giotto has considered the composition, discovering the power of framing a scene and guiding the viewer’s eye to its focus. It is a very human picture, religious or not you cannot help but be moved by it. I find Mary’s face especially touching, she bends over him with an expression of pure heartbreak.

The whole image has movement and atmosphere, light and shade gives the scene depth and the figures weight. The people are articulated within the space, their poses and proportions have been depicted realistically. This is where Giotto breaks from tradition. He is applying rules of perspective which were not formally practised by artists until the Florentine Renaissance in the 15th century. There is also an attempt to include us in the scene, something which had not really happened before in religious art. While the faces are not totally individualistic (long slitty eyes are Giotto’s thing) they are certainly not all based on the same face. Ciambue’s faces show the archetypal Byzantine faces, long with aquiline noses and almond-shaped eyes, their woodenness enhanced further by golden brown tones. Giotto has studied different people expressing grief in different ways, some quiet and others in utter despair. From the image below, a depiction of the same scene done some 150 years later in Greece, you can see how primitive art was elsewhere and how modern Giotto was in comparison. To me this signifies the start of the Renaissance; a breaking away from the pictorially stylised Byzantine/Medieval/Gothic model of flat, generic, alien looking people, sized hierarchically and contorted in impossible positions in unconvincing space. Telling the word of God in a visually convincing way makes the story real, relatable and brings it into our realm. I don’t think that there is anyone before Giotto who did this. Perhaps they saw no reason to. Massaccio, Piero della Francesca and Fra Angelico were to follow in Giotto’s footsteps and develop his ideas further, cementing his contribution to the progress of Western art.