Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cezanné

Royal Academy of Arts, until 10th April 2015.

Rubens (1577-1640 ) is a name we are all familiar with, even if we cannot name a work by him we could have a go at describing one. Dramatic, extravagant, fleshy, in the Baroque category. We could use the word ‘Rubenesque’. And yet for some reason his reputation is not quite in the same realm the mighty Michelangelo, da Vinci or Raphael. He is certainly an artist who has always divided opinion. I am not entirely sure why this is, Rubens’ works have power, beauty, ingenuity, and, as this exhibition proves, an influence which has resonated through the centuries to the present day. So vast is the exhibition that I have visited four times to do it thoroughly. I have tried to be very strict and only choose a few things to talk about, which goes against my rambling nature so please bear with me!

I confess that my love of Rubens is one I often forget. His biography is a fascinating one. By fourteen years of age he was apprenticed to two of Antwerp’s leading painters, and at 23 he was traveling around Italy admiring the works he had been copying as a student. Of all the paintings he saw those by Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto, the great Venetian masters, were to have a lasting effect on the young artist. While in Mantua the Duke of Gonzaga became his first noble patron, propelling him into a world of wealth and extravagance. He was sent on a diplomatic errand by the Duke to King Philip III of Spain, and spent a year at the Habsburg court. This time in Italy and Spain was vitally formative for Rubens both as an artist and an employee to elite patrons. In 1608 Rubens returned to Antwerp and opened up a studio, finding that there was a high demand of art from the wealthy merchants there. He was inundated by commissions for work and applications for employment (Rubens’ great protégé Anthony van Dyck (1599 – 1641) came from this workshop). The following year Rubens became court painter to the Spanish rulers of the region, Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella. By now he was well practiced in the art of politics and he acted as a sort of ambassador for them. At this time he was the most famous artist in Europe, receiving patronage from royalty, aristocracy and the Church.

The rooms at the Royal Academy are sorted thematically; Poetry, Elegance, Power, Compassion, Violence and Lust. The first room focuses on his landscapes and the artists who were influenced by them. This is the subject Rubens turned to in his last years, after retiring to the countryside he found inspiration in nature, weather and rural life. After painting the rich and famous choosing to depict country-dwellers must have come as such a refreshing change for the artist. Visual links to Turner and Gainsborough are made in the room, but I think that it is Constable who really absorbs the essence of Rubens. He said of his predecessor that ‘in no other branch of art is Rubens greater than in landscape’, which shows Constable’s high regard for him. The comparisons between the artists are particularly poignant in their observations of the effects of natural light (sunrise, sunset, moonlight). Evening Landscape with Timber Wagon (1630-40) especially brings Constable to mind; a large portion of sky, detailed trees and plants, and a rolling vista of land. The depiction of light is really quite beautiful, the way the last rays of sunlight filter through the overcast sky and give everything an ethereal tone. The peacefulness contrasts with the cart and its driver struggling to get home after a hard days work. In the same room is a sketch for Constable’s Hay Wain which shows a similar elegant composition and humble pastoral subject matter. The landscape as a subject was very much a Flemish tradition in Western art, and Rubens was continuing the heritage of painters such as Jan Bruegel the Elder (with whom Rubens often collaborated) and Jacob van Ruisdael. This is a side to Rubens I didn’t know about.

Evening Landscape with Timber Wagon (c.1630) by Peter Paul Rubens, oil on panel, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The room called ‘Elegance’ was my favourite. Rubens was one of those painters who could capture the essence of a person in their portrait, through a glint in their eye or the positioning of their hands. For artists of the 18th and 19th centuries he became the prototype. The great Joshua Reynolds was especially enamoured with him, and insisted that all pupils at the RA study Rubens closely. Thomas Gainsborough and Thomas Lawrence became Rubens’ heirs of portraiture, much in the same way that he had continued the traditions of painters such as Titian. Typically the works were of high society done at full length, with swooshing drapery and elements of classical architecture as a backdrop. The room is full of beautiful things, notably some glowing Lawrences, but it is dominated by the vast canvases of Maria Grimaldi and her Dwarf (c.1607) by Rubens and Genoese Noblewoman with her Son (1626) by Anthony van Dyck, which stand side-by-side. The compositional and stylistic similarities are obvious. The painterly depiction of surfaces are astounding, especially the fabrics. The ladies here both sit proudly, enshrouded in rich black dresses (colour of the rich) and rather lovely lace ruffs. Ms Grimaldi’s is particularly grand, making her head look miniscule in comparison. The ancient temple-like architecture with Corinthian capitals behind them adds to the grandeur of the image. The ladies sit in high backed chairs on Turkish looking rugs, and are accompanied by a servant and dog, and son and a dog respectively. They emit power and pride, of a motherly kind in van Dyck’s painting. Rubens paints his models to face us, where as the Genoese noblewoman is too important to acknowledge us. Today images like these are familiar to us, seeing their type in every grand house or art gallery. But Rubens was continuing the traditions of portraiture from the Renaissance, and the popularity of his work in turn influenced other artists.

In the Low Countries Rubens was primarily known as a religious painter. Many churches boast altarpieces by the artist and his studio, most famously Descent from the Cross (1612–1614) in Antwerp Cathedral. The room named ‘Compassion’ shows how Rubens brought a human element to Catholic painting using extreme emotion paired with strong realism. Christ on the Straw (1617) is the centre panel of a triptych, a three panelled folding altarpiece, and as such it has a function; to evoke piety in the person looking upon it in prayer or while taking communion. Painters working for the Catholic Church after Council of Trent played on the viewer’s compassion in order to promote religious reflection in an accessible way. Hence there was a shift towards realism and compositional design which included the onlooker in religious scenes. Here Jesus has just been taken down from the cross, his heavy corpse is almost as white as his shroud, his lips are grey and his skin is marked with dirt and dried blood. The faces around him create an arching halo shape, each one is individualistic and expressing intense feelings that should be mirrored in us a viewer of this holy scene. The drama is all in the simplicity, the scene is pared back to the essentials, to the people at the core of the story. The tones of light and shade are very striking, putting a kind of spotlight on the action. The almost life-size scale and the way knee of the slumped Christ breaks into our world includes us in the scene. It shows the brilliant versatility of Rubens, he could turn his hand to any genre. He does religion in such a vivacious way, yet retains an essential human element that we can relate to. His biblical works were highly influential, particularly the aforementioned Descent from the Cross which was in circulation through copies and prints. Gainsborough’s wonderfully energetic Sketch after Descent from the Cross (1766-69) is in the room, hanging with other studies and etchings by the likes of Rembrandt and Eugène Delacroix. I think it is Rubens’ originality and dynamism that stirred up so much admiration. And although what Rubens did for religious painting was not new (he was directly influenced by Caravaggio, for example) he did breathe a new life into it, and one which is distinctly his own.

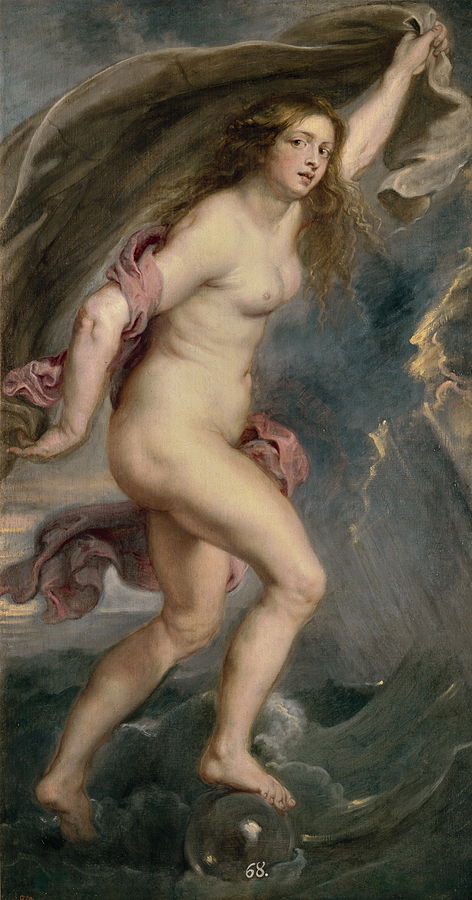

Lust must be considered over all themes to be Rubens’ forte. His female nudes were not the Renaissance ideals of long slim bodies with skin the colour and texture of marble. Those women are untouchable, and quite frankly would you want to touch them? Compare Botticelli‘s Venus to Rubens‘s Fortuna (1636-7) for example. She looks real, warm and softly curved. Like his other women she is the definition of health and fertility. And as the goddess of Fortune she should look thus. To the left the seas are calm, but she glides towards the storm. But she is a figure of bravery and strength. Her golden locks are not neatly styled, her face is uncertain, much as fortune is. I love the colour palette, the creaminess of her skin, the complimentary pink of her shawl, cheeks and lips, and the green/blue of the sea and sky beyond. The light breaking through the clouds on the right is done with great effect. There is a hint of eroticism, especially in her gaze and the brazenness of her nudity. But I think that there is also a tenderness and respect on behalf of the artist. I don’t see this or any other of Rubens’ nudes as objectification of the female. On the contrary I think he liked to look at a well-formed woman, and understandably so. This is woman as goddess, as a power over man. The legacy of Rubens’ nude is vast; Rembrandt, Boucher, Fragonard, Watteau, Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, Lucian Freud and Jenny Saville all show his influence.

Known as a charming and learned man Rubens thrived in the monopoly of Europe, a place of religious tension and political divide. Curiously he was of the same generation as Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Velázquez, but I think they are generally considered more famous. Seeing Rubens’ works displayed thematically and among paintings by artists whom he inspired allows us to see him in a whole new light. Most impressively is the effect he had on the course of art history, which is hard to imagine Rubensless. There is a distinct Flemish attitude to all of his paintings (an acute observation and obsession with surface texture and typical Northern European disregard of ‘ideal’ beauty) but it is balanced with an Italian flair for drama and innovation. He both honours the traditions of Western art and makes bold strides into unknown territory, like all the great masters. It is interesting that although many great artists after Rubens drew inspiration from him, there were some who detested him, most famously William Blake, Pablo Picasso and Van Gogh, who thought him ‘superficial, hollow, bombastic’. I think that anyone who does not have a taste for the Baroque may think Rubens over the top and gaudy. But taste needs to be disregarded to consider pure genius.

Rubens was a complete original, with relentless energy and daring. He brings paint to life, makes colours glow and glorifies every subject he touches. What I love most about Rubens, specifically his religious works, is that he doesn’t just depict something he breathed life into it. He painted operatically with an astounding eye for detail. He was known to use a paintbrush with just one hair. Anthony van Dyck, Rubens’ star pupil and heir is a master in his own right, but he is a man of a different temperament. Rubens said that his gift was ‘by natural instinct’. Wherever he got it from his legacy stands testament to it.