The Story of Women in Art

Amanda Vickery

May 2014 BBC 2

Still being very behind on my TV recordings, I watched all three episodes of this series last week. I must admit I was prepared for a three hours of an extreme feminist take on art history, but in fact I found the programme to be very objective and broad in subject. There was a little bias towards the female artist, emphasis on the downtrodden and repressed women artist. Vickery was very passionate about that, and before watching this I just accepted that that is how it was.

Vickery begins the story in the 18th century; The Georgian period in Britain which dominated by the likes of Reynolds, Turner and Adam. The Royal Academy of Arts, formed in 1768, has two women among its founders; Angelica Kauffman (1741 – 1807) and Mary Moser (1744 – 1819). There was an atmosphere of change in London, and the inclusion of these two women is evidence of the onset of a liberal feeling in the arts. Kauffman was a celebrated painter of portraits and genre, painting in a Classical style formal training and intentions of being a painter as a profession. Moser is notable for her botanically exact paintings of flowers, who was patronised by Queen Charlotte. Kauffman is particularly interesting as she tackled the subjects of men, history and genre painting. Regarded as the highest subject in art for the philosophical and intellectual connotations, the depiction of which required a thorough knowledge of anatomy, something respectable women were not supposed to be privy to. Of course life drawing classes went on at the Academy, but women were not permitted to attend. Already there is a sense of inequality, even in an institution which sought to be progressive.

Elizabeth (née Farren), Countess of Derby (c.1788) by Anne Seymour Damer, marble bust, National Portrait Gallery, London

I had never heard of Anne Seymour Damer (1749 – 1828) until now. As well as being an astounding painter she was the first British female sculptor. A thinker and a maker, her talent was unbridled when it came to art. From an aristocratic family Damer worked in paint to a modern Reynoldsian style, but as a sculptor she was a Neo-Classicist. And what a formidable women she must have been, to take up not only as an artist, something quite radical, but as a sculptor, something wholly unladylike. Wielding a hammer and chisel she created monumental carvings worthy of the great masters of the art. And whats more she often used women as the subject of her works, glorifying the female form. The 19th century saw women becoming bolder, stepping away from the weaker art forms of needlework and other domestic activities and entering the male domain.

Episode 2 moves across the continent to Italy to find another sculptress, Properzia de’ Rossi (c. 1490–1530) who was the first female artist of the Renaissance. She must have had a good reputation because Vasari takes note of her in his Lives of the Artists in the 1550s. Sculpture in Florence was very important, as it was a public symbol of the city’s power and dominance, think Michelangelo’s David or Cellini’s Perseus (both, indecently, male subjects). The life of a Renaissance woman should be private, confined to the home with the priority of family. To venture into the outside world, to seek a career other than housewife was radically original. Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532 – 1625) was another Renaissance woman who refused to be hidden away. She was fortunate enough to be from a family that encouraged creativity and intellect. After receiving formal training in painting she travelled to Rome, where she met Michelangelo who praised her natural talent, and then to Milan where she was spotted by the Spanish nobility there and dispatched to Madrid to paint for the monarchy. But, upon arriving at King Philip II’s court she was not given the title of royal painter, but lady-in-waiting! Despite this blatant insult she gained wealth and reputation. Her femininity comes through her art, applying a tender and emotional depiction of subjects. There is a sense of domesticity in her painting The Chess Players, you can sense the ease of a family at play.

Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614–20), Artemesia Gentileschi, oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Now Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – c. 1656) is a woman artist I had heard of. Trained by her father Orazio Gentileschi she was creating masterpieces by the age of 17. At 19 she was raped by an art teacher, but she refused to let it ruin her. Instead used her experience to infuse her painting with emotion and female dominance. Her take on Judith Slaying Holofernes (c. 1611, done while the trial to persecute her rapist was going on) shows a fiercely formidable woman, both physically and mentally strong. As well as securing the patronage of wealthy nobles such as the Medici, Gentileschi went on to become the first woman to be accepted into Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence. Not only was she successful as a woman artist but her usually female-based subjects were both admired and in demand. Throughout her career she worked in Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples and London, where she and her father were court painters to King Charles I. Although there were other women painters before Artemisia Gentileschi, few share the popularity and regard that she still holds today.

Jumping to 1850 in the final episode Lady Elizabeth Butler (1846 – 1933) is another woman of whom I know nothing, though I know some of her works from sight. She became famous for her visions of war, quite extraordinary as being a Victorian woman she had no first-hand experience of it. Vickery remarks that her reason for choosing this subject was not only due to her love of history, but her desire to depict the human element of it. One of her most famous works, The Roll Call (1874) caused a scandal when it was shown at the Royal Academy of Arts, the police were called to disband the riot. But Queen Victoria brought the painting, and she achieved fame. John Ruskin once said ‘no woman can paint’, but after seeing The Roll Call he admitted he was wrong. As well as showing her talent as an accomplished painter the emotion and sensitivity of this work is astonishingly moving.

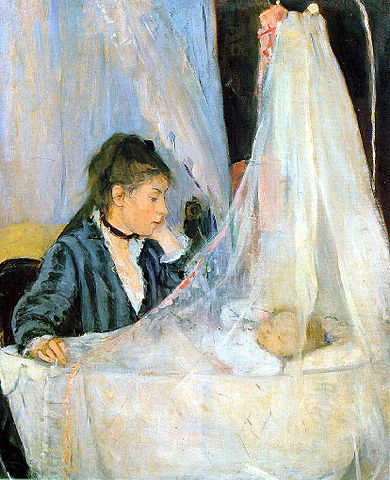

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) was another woman who’s reputation has endured to the present day. When her works come up at auction they go for millions. But nowhere near the amounts fetched by her Impressionist contemporaries. She was a friend of Manet and his artistic circle; she actually went on to marry his brother. She was a rule breaker, capturing life through domestic eyes. Whereas her fellow artists were painting things like urban street scenes her images are portraits of the home and family life. But I don’t think she was compromising, she clearly painted what she loved and held meaning for her. The Cradle (1872) is a picture that epitomises maternal love. The woman tenderly gazes upon her sleeping baby. She is probably tired and in need of sleep but the fact that she would rather watch over her child makes for such a sweet picture. Perhaps her ability to depict female sentimentality hindered her, perhaps if she had decided to paint waterlilies or scenes of Parisian nightlife she may have achieved greater fame. But Morisot’s career was her choice, she came from wealth and did not need to earn money. She died at 54, and even in death Vickery points out that her grave is beneath her husband and famous brother-in-law.

The woman Vickery has chosen to illustrate the significance of women artists has truly proved her point. Although I have only picked out a few here, and omitted the creators of craft and fashion, the broad examination of the female imagination proves what we already know; that women have just as much creative imagination and artistic ability as men. But it is interesting to learn about the battle women fought to be allowed to be an artist by profession, as it is something taken for granted today. I for one have a new-found gratitude for the women with ingenuity who fought for art.