Goya: The Witches & Old Women Album + Renaissance Modern: The Gilbert & Ildiko Butler Drawings

Goya: The Witches & Old Women Album – 26 February – 25 May 2015

The Courtauld Gallery, London

To me Goya is one of those artists who totally changed ideas about what art can be. I find his works express a side of human creativity which is not often (and certainly was never traditionally) considered the stuff of masterpieces. History, myth and religion were always regarded as the worthiest subject matter. The likes of Michelangelo and Raphael hold the status of ‘master’ for very good reasons, replicating nature and observing the human form in through that quintessentially Renaissance mode of beauty – the ideal. But Goya, who I think had a predisposition for the macabre, shows us that everything is worthy of depicting. The unusual and ugly inspired him more than perfection. While in a sense he followed the tradition of Western painting (particularly his predecessors Velazquez and El Greco) Goya transformed subjects through his own idiom and stands out as an anomaly. I think it is important to note that these sketches were never meant to be seen by eyes other than the artist’s. They are personal and private, a sort of visual record of thoughts. The projection of our own ideas and feelings towards them are irrelevant, but nevertheless this sneak peek into Goya’s unbridled imagination is a priviledge.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) was a Spanish painter and printmaker who spent much of his career in the service of Charles III and his successors Charles IV and Ferdinand VII. He painted the royal family extensively, but I wouldn’t say that portraiture is his thing. He certainly didn’t flatter the sitter, a family not renowned for being overly attractive to start with. He was a masterly draughtsman and drew continually throughout his life, mostly from the life around him. Of around 600 known sketches 23 are on display in the Courtauld for this exhibition. What soon becomes obvious that Goya had an obsession with the grotesque. Wicked Woman (1819-23) is a disturbing image of an old crone, with a skeletal and leathery face who is appears to be eating a baby (my image is not the one on display, that one in fact had red pencil highlights about the mouth and infant’s body). It brings to mind Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Son which was done around the same time. Here the balding woman kneels before empty plates and bowls, perhaps so hungry that she has been forced to cannibalism. With a dark nun-like veil about her head she looks out at us. Her open mouth shows a few crooked teeth. It really is quite a horrid image, made worse by the fact that even though we have caught her in the act she doesn’t look at all surprised or remorseful. She grasps the infant by the arm and behind, its head tilts back in an almost audible scream.

During the time Goya was active various printing techniques were being developed, and the artist experimented with the different methods extensively. Lithography, invented in 1796 was first used as a cheap method of large print runs of theatre flyers, but artists found that it made for an atmospheric way of printing images. Using the repellant qualities of oil or wax to create areas of saturation on an etched plate it allowed for an extreme contrast of light and dark (chiaroscuro). The Monk (c.1819-22) is one of Goya’s first lithograph, and it shows how effectively he used the qualities of the method to his advantage. The very black inked-up areas leave us not knowing what is happening while the exposed white of the paper puts emphasis on the subject, working like a spotlight. The monk’s habit emerges towards ot of the shadows, fists clenched, one holding a crucifix. We can just make out a vertical line of the nose and the glint of two eyes looking out at us. At the time there was much social unease about the corruption of religious orders and Goya’s works often hints at the suspicions of vice and peversion within the Church.

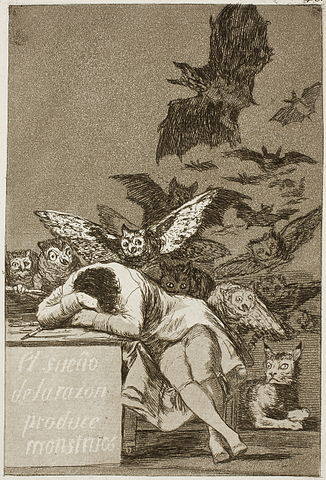

Probably Goya’s most iconic work on paper is The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (c. 1825-28), a print from his famous body of work Los Capricos (1797-99). In the series of 80 illustrations he produced a critique on his nation and “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society”. Weird and cryptic Goya uses reoccurring symbols throughout. Here we see the artist asleep at his desk, and unconscious he is being plagued by owls (folly), bats (ignorance), and other strange creatures, representing darkness of both the night and the mind. The caption below reads “Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels”. Goya continually returned to themes of nightmares in his later career, perhaps a fear of the subconscious and uncontrollable madness locked within. Poet and artist William Blake also explored themes of insanity and the supernatural, and like Goya he projected a satirical view of social and political issues of his time.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (c. 1825-28) by Goya, etching, aquatint, drypoint and burin, Prado, Madrid

Goya came from a rural town and worked hard to achieve success, he wasn’t one of those privileged young artist with good connections. I think he had a love of the common people and provincial life which stayed with him throughout his career. Like da Vinci he seems to have revelled in drawing what was around him, the more wrinkled and grotesque the better. In the sketches here Goya uses physical aging to show weaknesses of the mind; folly, vice and often depravity. There is a zombie like quality to some of the elderly figures, they seem fragile and soft as though modelled from clay. Some are depicted with a delicacy and almost tenderness, perhaps sympathising with those experiencing what inevitably awaits us all. Goya’s apparitions appear in the stroke of a few lines and a swish of ghostly grey wash. With an unflinching eye he observes the decay of the human body and mind with a dark sense of humour, not unlike that of William Hogarth or William Shakespeare. This wonderful exhibition brings us close to Goya in a way his grand finished paintings cannot, and for that opportunity must feel extremely privileged.

Renaissance Modern: The Gilbert & Ildiko Butler Drawings – 22 April – 7 June 2015

Alongside the Goya exhibition is this lovely one-room display of drawings from the Courtauld’s amazing collection, curated by the students there. As with Goya we are allowed a more up-close and personal experience of masters such as Allori, Barocci and del Vaga.

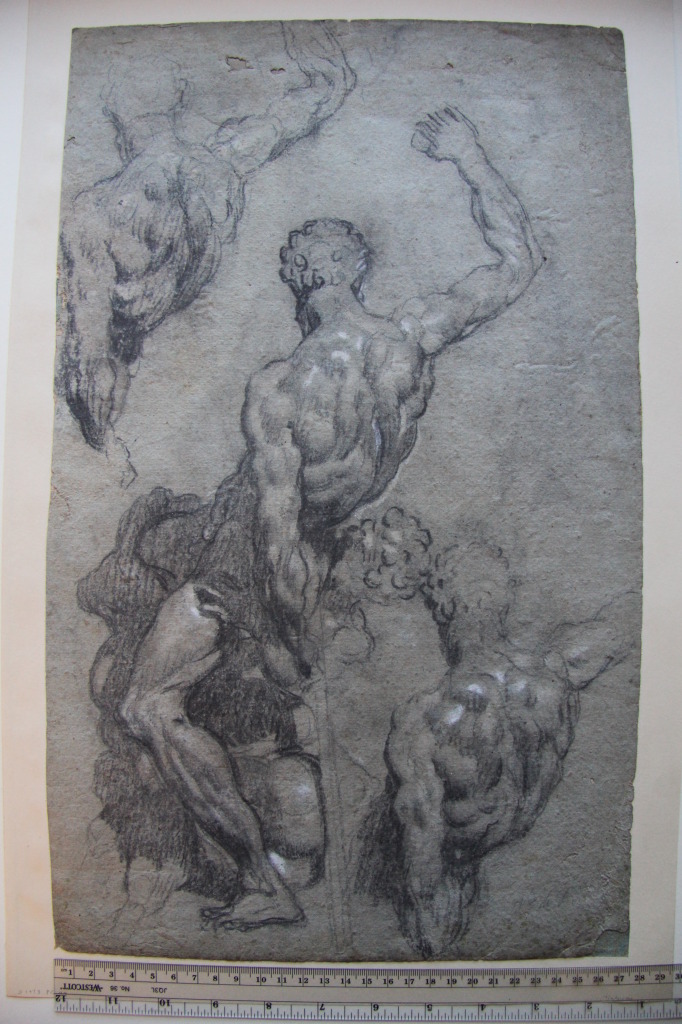

A beautiful sketch by Tintoretto of Samson and the Philistines (1550-55) after Michelangelo‘s lost sculpture was the first thing to catch my eye. We see the muscular back of Samson, a rock in his hand, as his assailant bites his backside. The exaggerated rippling flesh of the protagonist’s back narrate how Samson was given superhuman strength from God in order to defeat his enemies. We also see his head of curls, which the temptress Delilah later hacks off.

‘Samson and the Philistines’ after Michelangelo (1550-55) by Tintoretto, black chalk with lead white heightening on paper, Courtauld Gallery, London

Parmigianino‘s preparatory sketch of Conversion of St Paul (1527-30) in black chalk shows the artist’s wonderfully rapid technique, a quality which does not translate through his finished oil paintings. I love the fact that he could create such drama, weight and movement through so few lines. The elongation and muscular tension give away his Mannerist style. The final painting of this subject is almost identical to this compositional drawing. It at once shames and amazes me that this amount of energy can be created with a bit of chalk.