Radical Geometry: Modern Art of South America (from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection)

Royal Academy of Arts, London

5th July – 28th September

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/radical-geometry

Upon entering this exhibition I felt out of my comfort zone. I knew nothing of the era, I had never heard of the artists (despite my Art History degree) and only one of the many artworks on display was familiar. However the things I saw in the first room soon sparked stylistic images setting a time and place for the exhibits, which are conveniently curated by country. What the visitor going into this exhibition has to understand is the socio-political and cultural environment from which the art came.

On the whole South America saw a renaissance of sorts at the start of the 1900s, one which was born from financial, political and general social stability. This sense of optimism, strength and confidence infiltrated into culture, and most importantly, art. Artists were free to express feelings through their work, and did so in a collaborative way through the formation of groups. Migration from other countries meant a circulation and exchange of ideas. The cities the rooms in this show represent all demonstrate a common attitude and set of values shared by artists in their friendships and partnerships. Each has their own particular artistic vernacular, but all are reactionary.

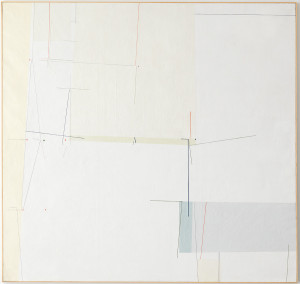

Development of 14 Themes (1951-52) by Tomás Maldonado, oil on canvas. Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ©

In the first room, dedicated to Uruguayan artists, Tomás Maldonado’s Development of 14 Themes (1951-52) caught my eye. It is different to anything else in the room. The tonality in particular contrasts with the canvasses of bold bright blocks of colour that surround it. The gentle white of the background and subtly coloured lines and dots allow the eye to roam over the canvas, much like a map. As a viewer we are free to feel our way around and read the image as we wish. This painting (like most in the exhibition) made me think of music. To me it this painting is jazzy. But like a quiet slow-paced Miles Davis piece. It is harmonious, and the empty space allows contemplation. The shapes can be jumped to and from, creating a very personal experience of a narrative. It is interesting that this was Maldonado’s last work as a painter. Being a Communist he thought art had become bourgeois and elitist and so moved on to architecture, a branch of design that he thought more accessible.

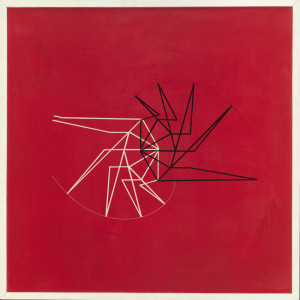

Visible Ideal (1956) by Waldemar Cordeiro, acrylic on masonite, Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ©

Visible Ideal (1956) by Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordiero looks like it was made by a machine. It is so geometrically precise, it is reminiscent a spirograph. Along with the pared down colours of red, white and black it is visually striking, diagrammatic. Like many other of the artists here Cordiero sought to create something new and fresh. He used industrial materials and tools which give a design-like quality to his work. Lines intersect one another and create patterns. It is not surprising that he was an admirer of the Russian Constructivist movement. But I think there is an organic element to it. To me the shapes are like fossils or shells. You can imagine finding this image in a science textbook. Cordiero would later go on to work as a designer, illustrator, urban planner and art theorist and critic, and to me this image betrays his love of design as theory, theory as design.

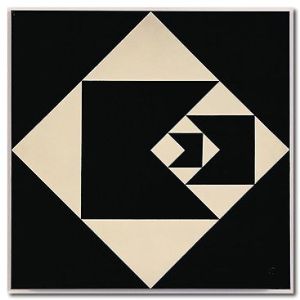

Diagonal Function (1952) by Geralto de Barros, lacquer on cardboard, Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ©

Geralto de Barros‘ Diagonal Function (1952) is the one painting I knew, having seen in a book many years ago I remember the striking image. Like Cordiero he was a part of La Ruptura movement. Founded in Sao Paulo in the 1950s the group’s manifesto involved creating personal not political art. It was anti-establishment and anti-tradition, rejecting what had gone before in order to make original art with an original visual language. Like the Constructivist and De Stijl artists elsewhere in the world, the aim of the group was to break with the past and create something new, playing a critical role in South America’s Avant-Garde art scene. De Barros was a man of many artistic skills. He was a graphic designer, photographer and furniture designer. Diagonal Function demonstrates his graphic skills. This piece has a strong geometric focus, the result of a play with scale and interlocking shapes. Again the use of industrial materials, lacquer on cardboard in this instance, add to the feeling of modernity. Although flat to the eye, the shapes have dimension and depth. It looks like a symbol or a logo. This piece shows a forceful movement towards extreme abstraction.

The modernity of Jesus Soto’s Nylon Cube (1990)resonates in a timeless way. The Venezuelan artist was associated with Kinetic and Op art, pioneering a style in South America influenced by the European movements. This piece combines the two. Hundreds of vertical painted nylon strings are pulled taut by two white blocks. A cube magically appears within the strings, it is shimmery and transitory. But this is beyond geometry. This sculpture look different at every angle. Walking around it is a bit disorienting, and our position as a viewer alters what we are viewing. Like most of the artists in the exhibition there is an interest in spectator participation. Essentially our perspective changes the artwork. It is at once opaque and transparent, solid and delicate. I found an interesting quote on Soto’s website, which although lengthy shows the thought process behind an otherwise puzzling piece; ‘In the future as in the past, my art will remain linked to the uncertain, taking care not to try to express the permanent, the unchangeable. For I have never sought to show reality caught at one precise moment, but, on the contrary, to reveal universal change, of which temporality and infinitude are the constituent values. The universe, I believe, is uncertain and unsettled. The same must be true of my work.’ This particular artwork is an expression of something unmarred by time and constantly subject to change.

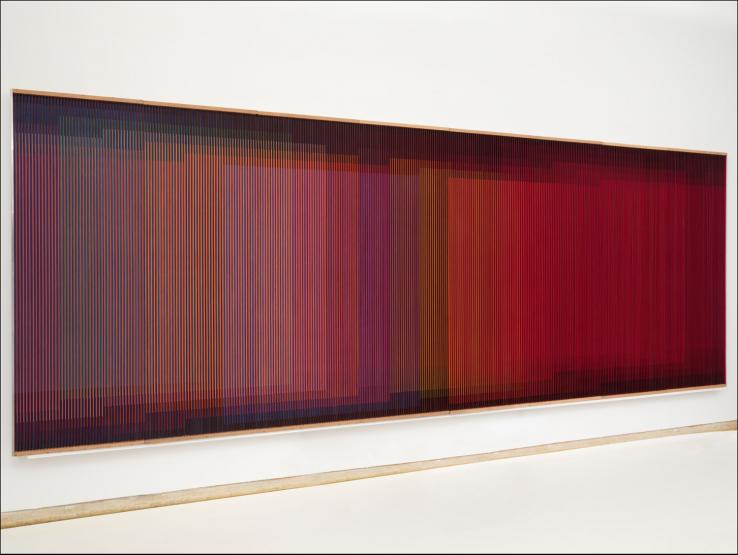

The exhibition closes with Physicromie no.500 (1970) by Carlos Cruz-Diez. Like Soto’s Nylon Cube it has a feeling of transience. By looking at and moving around the piece it comes to life. In a video on the Royal Academy of Arts website with Cruz-Diez (found here: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/carlos-cruz-diez-in-conversation) he very eloquently explains of his early career that ‘it was a little boring that everybody was painting the same way. And I asked myself isn’t’ there any other way of painting?’ He investigated colour and the effect of light, form, space, perspective, very much as the Impressionists (whose work he admired) did. The result of his research is the Physicromie series, a word created by Cruz-Diez to describe the physic, or the physicality of chromie, colour. Physicromie No. 500 is unlike anything I have seen. A long rectangle of colours created by strips of red acrylic, the image changes with the slightest movement. From face on we see a row of layered squares with a reddish-purple hue. Moving from left to right one can see a spectrum, the colours move with you revealing a rainbow across the image. But, looking down either end the whole thing is red. From different angles different colours appear. Interaction through movement brings the piece to life. Optically it challenges us as a viewer. It gives us a part to play rather than just standing in front of it. In the video mentioned above Cruz-Diez uses the example of a white sheet of paper to describe his investigative work. From most perspectives it is just a white sheet of paper, but when moved around will absorb different tones through light and reflection. This concept is transformed into an artwork here.

Physicromie No. 500 (1970) by Carlos Cruz-Diez, casein on PVC and acrylic strips on plywood, Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ©

We know that throughout Art History cities like Florence, Paris and New York have been the artistic capitals of the world. But few realise that cities in Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela were hotbeds of creative originality. While the Europe and America had movements like Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, South America had its own unique reaction to the world. Geometry was adopted as a new visual language for artists. They were not just concerned with art, but design, politics, philosophy. The choices an artist made when creating their work showed intention and control. But behind the rigid shapes and bright colours is something very human. After all one would not feel moved by anything in this exhibition if there was no emotional element. To quote Soto again ‘From all the universal values…one idea stands out above the others – relations’. This is what the artists of this exhibition want from us as a viewer, a relationship, a connection. Without us the artworks are dormant. In a time of prosperity and modernity in Latin American countries there was a feeling of optimism, change and independence which, however non-figurative, can be understood through the art in this exhibition. They believed art could make the world better, and that sense of freedom and experimentation is inherent in every work of art here. Their ideas are certainly radical, but what struck me most is that they show how geometry can be more than just maths.

All images from www.royalacademy.org.uk, with the exceptions of Soto’s Nylon Cube (Benedict Johnson) and Cruz-Diez’s Physicromie No. 500 (www.lainvencionconcreta.org)