Rembrandt: The Late Works

15 October 2014 – 18 January 2015

Although I was desperate to see this exhibition I held off for nearly a month in the hopes that the inevitable crowds had already visited; but my optimism was in vain. Seven rooms of the Sainsbury Wing were absolutely heaving with people, which eliminated any enjoyment of the experience and meant that I could not get near around half of the works on display, but the feeling of standing before a Rembrandt could not be ruined. And every chance I had to squeeze into a gap in front of my favourite works were selfishly savoured, my eyes pouring over every inch of canvas.

The first room was especially wonderful. It contained four large self-portraits all done between 1659-1669, each conveying a different emotion, a different mood. Rembrandt’s face is almost as familiar to me as my own, and seeing these paintings together articulate that despite painting himself around fifty times (not to mention the drawings or etchings) he has something new to show us with each one. As for most young artists early on in their career a self-portrait would provide both a readily available subject matter and observational practice. Rembrandt painted himself until the end of his career and his life, through his prosperity and suffering. The first portrait in the room, Self Portrait (1659), is open and honest although not exactly flattering. It is as if he is saying that his good looks may have faded, he may be more jowly and less slim than he was, but he has still got his technique. Ageing gives him the perfect opportunity to showcase his virtuoso skills of depicting texture and human emotion. With a shy and questioning expression Rembrandt looks out at us with a frank directness. I love that there is a winkling in his eyes, the impasto of the paint there emphasised further by the lighting in the gallery. The brushstrokes are masterly; from the thinnest of wisps of greying hair to the ruddy, doughy complexion of his once smooth cheek. His cloak and the background are less detailed, enhancing the sensitive attention to the important details. His ham-fisted hands express insecurity to me, they are loosely clasped reminding me of a gesture of worry. It is a very personal, informal portrait. It seems to serves no purpose but to chronicle his life, a visual diary entry of sorts. But for us as a viewer we are invited to examine the artist, to feel as if we know him. There is a hint of psychology within the portrait, something which the exhibition shows is something idiosyncratic of Rembrandt.

Themed around ‘Light’ room 2 is filled with etchings and drawings, of which I ashamedly admit knowing nothing of. Mainly of biblical subjects the prints show the methods used to achieve the compositional balance the artist wanted. The repeat of prints from the same block show an innate visual understanding, Rembrandt experimented to perfect a scene’s format, even testing different papers for their effects. One cannot help but think of Caravaggio upon seeing these works; the strong directional light and the pools of dramatic darkness surely owe something to the master of chiaroscuro. The Dutch Caravaggisti who visited Rome in the early 17th century brought back the influence of Caravaggio to Utrecht, and although a generation older than Rembrandt he was clearly influenced, perhaps feeling an affinity to his Italian predecessor. Caravaggio’s approach to painting lent itself particularly well to the art of the Netherlands because of a common interest in nature and real life. Rembrandt grew up in Amsterdam, the capital of the Dutch Republic, which during the Seventeenth century was the wealthiest empire in Europe. Dominantly Protestant in religion, the nouveau riche merchants were Rembrandt’s clients.

The story which inspired Rembrandt to paint Lucretia (1666) comes from Livy’s Histories of Ancient Rome. Lucretia is a good Roman woman, the embodiment of wifely virtue, but arouses the interest of a corrupt Roman prince, who blackmails and rapes her because she denies his advances. Her husband and father arrive, and after explaining the attack she pleads that they avenge her, saying ‘…it is only the body that has been violated the soul is pure; death shall bear witness to that’ (The History of Rome, chapter 58) before plunging a knife into her heart. Lucretia the embodiment of purity and innocence, and the tragedy of her suicide has been depicted here with extreme sensitivity. The theatricality of her stance and dress make it appear as from a scene in a play. The drapery in the shadowy background contrasts with the golden-swathed heroine, who appears under a spotlight, about to stab herself with a dagger. Her free hand splayed in a gesture of despair, her heavy lidded eyes laden with the sorrow of her turmoil and the decision she has come to make. She looks to her right hand as if to urge it on. These extreme emotions contrast heavily with the resplendence of her dress and jewels, they are meaningless and do not redeem a wronged and disgraced woman. I love her expression, her whole face is relaxed in resignation and the artist has captured the expression of exhaustion.

Skipping ahead to the last room in the exhibition, and the second Lucretia painting (1666) which is a whole new translation of the subject. This time in the throws of death, dealing with the decision she has made to end her life rather than live a dishonoured woman. Taking her final breaths, she grips the weapon that has made the wound to heart, expressing the affirmation of her decision. She looks more dishevelled, her clothes are somewhat in disarray and her undershirt exposes her. The golden robes she had worn before are about her arms. She is more starkly lit, emphasising the white and gold of her clothes, a glint of a pearl earring and her pale grief-stricken skin in stark contrast to the obscure backdrop. This is the image of a martyr, a Saint Agnes or Agatha. Her embellished headdress catches the light in a halo-like way. Although dressed in opulent materials Lucrezia is by no means an idealised beauty, in fact she is quite plain. Her face embodies utter hopelessness and despair. What I love most about this painting, and actually most of Rembrandt’s faces, is the lips. I think he understood that while eyes can tell you a lot about a person, a mouth can portray an immediate emotion, be it a final exhalation as seen here, or a slight movement. Lucretia’s lips express her resolve but also a desperate sadness. This canvas is also the first on which that Rembrandt, or any other artist, uses a palette knife to apply paint. The build up of layers creates a multidimensional surface that provides more light. Although essentially still Rembrandtesque, this later version is looser, more fluid in technique.

More famously known as The Jewish Bride (c.1665), this portrait of a couple is one that takes on an biblical subject. Isaac and Rebecca are known as the embodiment of ideal religious matrimony. Here the gentleman, with one hand held tenderly against his wife’s chest, wears an expression of love and care, while his lady gently touches his hand, looking contented and at peace. It goes without saying that Rembrandt must have known what a happy marriage felt like to be able to depict this image so faithfully. His wife Saskia died in 1642 at the age of 29, after eight years of marriage and shortly after the birth of their fourth and only surviving child. Rembrandt was said to be heartbroken, and what here should be a happy image has an element of something else to it. The restrained colour palette, the burnt red and warm gold colours set against what appears to be a crumbling brown wall. The golden sleeve is surely the same material as those seen in both Lucretia paintings. The bride is bejewelled, wearing adornments on every par of her. They look resplendent, wealthy in life and love.

Portrait of a Couple as Isaac and Rebecca, known as The Jewish Bride (c.1665) by Rembrandt van Rijn, oil on canvas, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

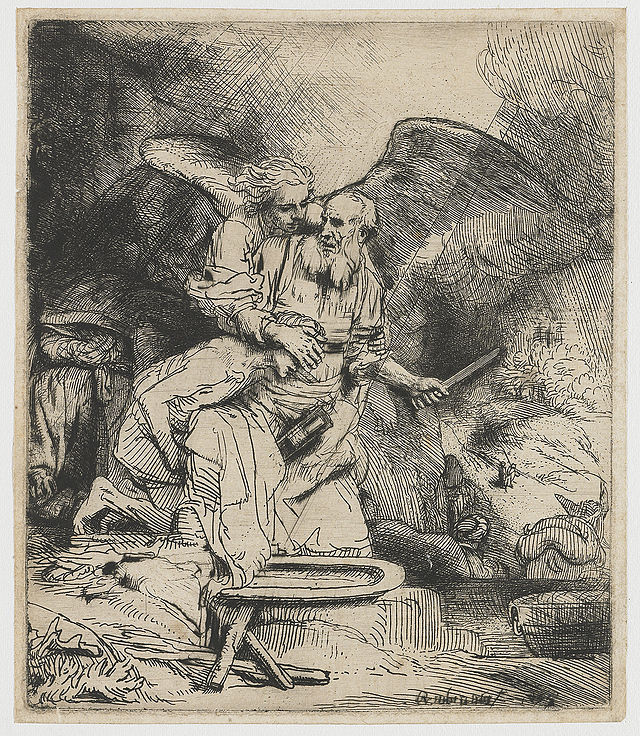

The seventh and last room, themed ‘Reconciliation’, holds some of the most moving and personal works in the exhibit. I particularly liked this etching, mostly because of Rembrant’s translation of the story, but more than a bit because of how it reminds me of Caravaggio‘s two versions of the Sacrifice of Isaac (c. 1598 and 1603) . It is also not totally unlike his Roman altarpiece The Inspiration of St Matthew (1602). There is something about the angel who breaks through to the human realm, leaving heaven to stop Isaac. Here as in Caravaggio’s, the angel grabs Isaac giving the scene a feeling of urgency, as if the angel was seconds from being too late. I love the look on Abraham’s face, the shock and almost deflation at the realisation at what he has nearly done. The bible tells of how both father and son were willing subjects to God’s command. It is a story I have never really understood, but nevertheless Rembrandt makes the scene very human. The varied cross-hatching depicts different textures, from the feathers of the angel’s wings, the vegetation on the rocky terrain and the slightly aged skin on Abraham’s strong knife-welding hand. There is a very high contrast between the untouched areas of paper and the very dense ink black shadows, which adds drama, emphasising the celestial being’s presence. Rembrandt’s grand canvas of the same subject from 1635 shows a totally different translation, one that is pure Baroque. Although a small etching, I think this image is far more moving than the painting.

Abraham’s Sacrifice (1655) by Rembrandt van Rijn, etching and drypoint on paper, The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

What I love about Rembrandt, and what this exhibition really brings to the foreground is the artist’s originality. Yes he was influenced by certain masters (my beloved Caravaggio included), but he was totally unique; there was no one like him before and there has been no one since to rival his particular style. The images all come from the same world, but it is uniquely Rembrandt’s world. And what makes him so great in my eyes is that his world is not very much different from ours. This cannot be said of all art from the 1600s. For want of a better word he is so ‘human’. I really could go on with this review, every work was a masterpiece in its own right. In short it was a blockbuster exhibition in every sense of the word, swarms of crowds and all.

p.s. If you liked this exhibition I strongly recommend reading Rembrandt’s Nose: Of Flesh & Spirit in the Master’s Portraits (2007)