The Art of Bedlam – Richard Dadd

16th June – 1st November, Watts Gallery

A couple of weekends ago I visited the Richard Dadd exhibition at Watts Gallery. I had heard of the artist and had seen an image of one of his paintings in a book, but I had not done my usual reading-up on him. This turned out to be a good thing, as I felt enlightened when I left the gallery. Richard Dadd (1817-1886) is not your stereotypical Victorian painter. While his contemporaries were tackling moral, social and political subject matter and creating new ways of painting Dadd was doing his own thing. As a student at the Royal Academy of Arts he was a star-pupil with a promising career ahead, but after a period of travelling he returned dramatically changed. While recuperating at his family home he killed his father, and was subsequently committed to Bethlem psychiatric hospital. From 1843 he spent his life in an asylum, and created a large and varying amount of art.

Dadd was a patient of Bethlem hospital (or Bedlam as it was more commonly known) for 2o years. During that time he created this, The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855-64). First of all it is necessary to say that this image does not do the painting justice, up close it is painstakingly intricate. Although a relatively small painting the artist spent years on it, and the bottom left section remains incomplete. It is bordering on illustration, the style and colours used remind me of a print in a children’s book. What is most striking is the fineness of the painting, the minutiae of detail makes it hard to reconcile the artistic and mental faculties required of this kind of work. The surface has a tapestry-like texture, parts appear to have been painted with a single-haired paintbrush with a microscope. The composition is curious, there is a spiral unwinding of narrative and the blades of grass dividing the scene make us feel as though we are peeking through the undergrowth. The fairies themselves are wonderfully weird, I particularly like the two ladies to the left with tiny waists and enormous calves, and the little grey man squatting fretfully by their feet. Apart from Oberon and Titania from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream towards the top of the canvas the rest of the story is Dadd’s, which he endeavoured to explain in a cryptic poem. With a spirit of folk story he carries on the bard’s themes “with shimmering white balletic fairies racing through the trees and up moonbeams”.

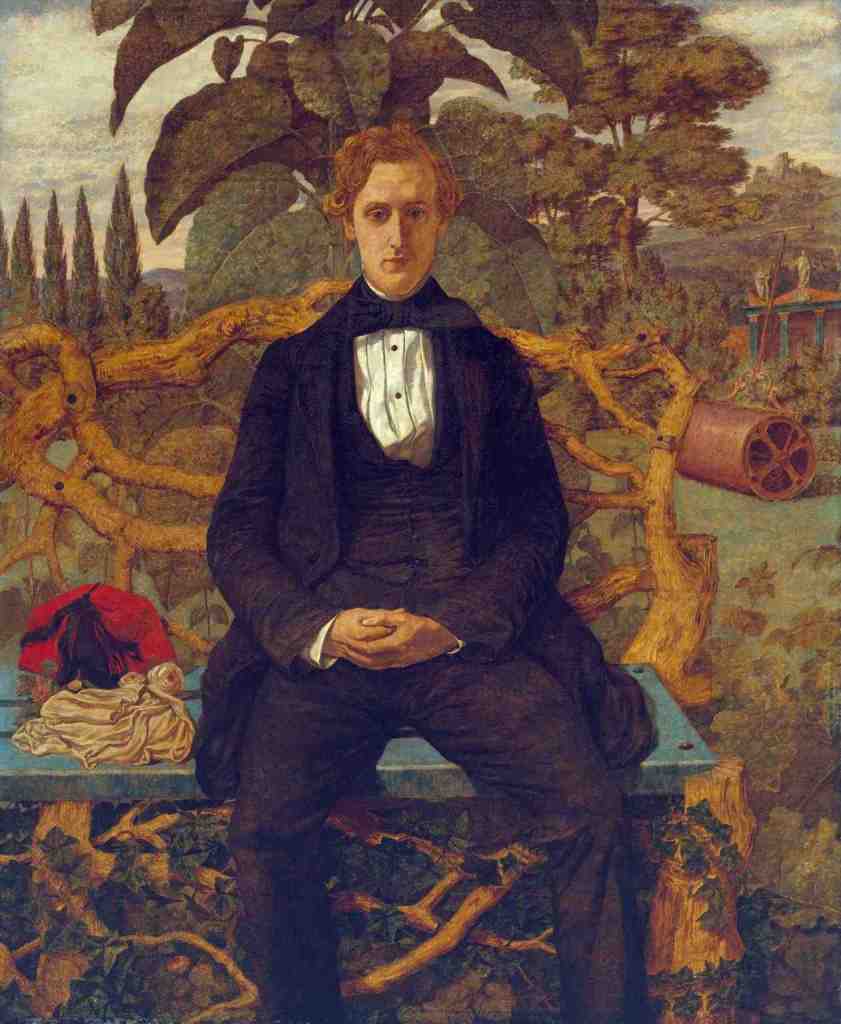

Medical notes from Bedlam say that Dadd “is very eccentric and glories that he is not influenced by motives that other men pride themselves in posessing”. But Dr Hood, Bedlam’s superintendent upon the artist’s arrival, clearly saw his genius and became a sort of patron to him. Dadd painted his portrait, in Portrait of a Young Man (1853),in a way which was unconventional for its time and remains so now. It has a melancholic air, perhaps it is more about the painter than the sitter. Although it is set outdoors it is not natural, in fact the background seems to be imaginary. It is strange and a bit unnerving, maybe a reflection on Dadd’s state of mind and own perception of the doctor and the institution. There is a strange sense of perspective; the sunflower plant behind the doctor with its gigantic leaves, his shapeless suit and the oversized fez beside him continue the illusion. The gnarled intertwined branches that make up the back of the bench are peculiar, as is the treacherously wonky classical building to the right. Cypress trees usually symbolise mourning. But the doctor’s face is kindly, his pose open, and he gazes at us (and Dadd) as one would look at a friend who is telling us something intimate. I think it tells us something of their relationship, and perhaps how Dadd felt as an inmate of the mental hospital.

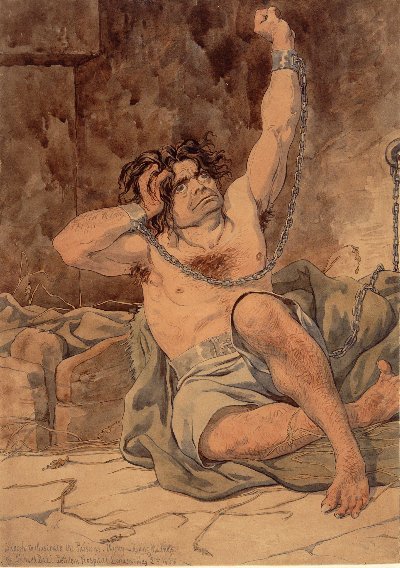

Another side of Dadd’s creativity was shown in the exhibtion through watercolours. In a series to illustrate Passions he depicted Agony-Raving Madness (1853), surely something he knew a bit about. In a time when mental illness was not understood and schizophrenia (what it is now thought Dadd suffered from) was not yet identified, this image can tell us a lot about what the artist’s experiences. I think it is the visual definition of what it is to suffer from mental illness. The man looks utterly exhausted and tormented from his psychologial pain. But although it explains the physical and mental feelings of being imprisoned in the illness I don’t find it as telling of the artist’s emotional state as the weird and often nightmarish creations from Dadd’s imagination. Referring back to The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke, the little grey crouching fairy is more unnerving and emotional to me.

Agony – Raving Madness (from sketches to Illustrate the Passions) (1854) by Richard Dadd, watercolour on paper, Bethlem Museum of the Mind

I love to discover new artists and learn about their lives, and this small yet varied exhibition gave a broad overview of Dadd’s story and his extraordinary works. Two things really stood out for me; firstly Dadd’s staggering talent as a painter, and secondly how clearly he visualised his ideas, be they fact or fiction, satirical or serious. His technique is exquisitely fine and individual. It is known that he did not rely on sketchbooks to plan out his work, and that he painted straight onto canvas from his imagination. He is unconventional in the best way, weird and wonderful. Although his life is overshadowed by mental health problems his art is amazing. As a patient of Bedlam he created some of his most wonderful works, which contradicts hospital reports of being ‘violent and dangerous’, ‘a thorough animal’. This intimate display of drawings and paintings show that Dadd tried his hand at many subjects in art, but seeing his work in the flesh makes me feel that it is his strange and enchanted fairy scenes that he really cared about, perhaps it was kind of an escape for him, his own mythical world in which he could be free. Speculation aside, it was an enlightening and beautiful exhibition.